Want to create a long-lasting institution? Serve alcohol.

Beer, wine, and spirits don’t necessarily call to mind heady, future-focused long-term thinking, but if one looks through any list of the longest-lived institutions in human society, it’s easy to see a trend arise: a surprisingly large portion of the organizations that have lasted for centuries or even millennia are places like breweries, wineries, bars, and inns. They’re places for weary workers to connect or for travelers to rest and revel. It’s a storied history, and part of why Long Now founded The Interval, our combination cocktail bar and library, in 02014.

It’s perhaps of no surprise, then, that alcoholic beverage consumption has been a key part of human ritual life since long before even the oldest surviving alcohol-serving institution was founded. A recently reconsidered archeological discovery from early Bronze age West Asia provides insight into how early human civilizations used alcohol.

When it was first discovered by Russian researchers in 01897, the Maikop kurgan provided a wealth of information on the luxuries that elite status afforded in what became known as the Maikop Early Bronze Age Culture, which thrived in the Western Caucasus Mountains in the fourth millennium BCE. Dated to approximately 03300 BCE, the kurgan was a burial mound for three individuals filled with funerary artifacts and status symbols, including ceremonial figurines, weapons, and finely worked metal jewelry.

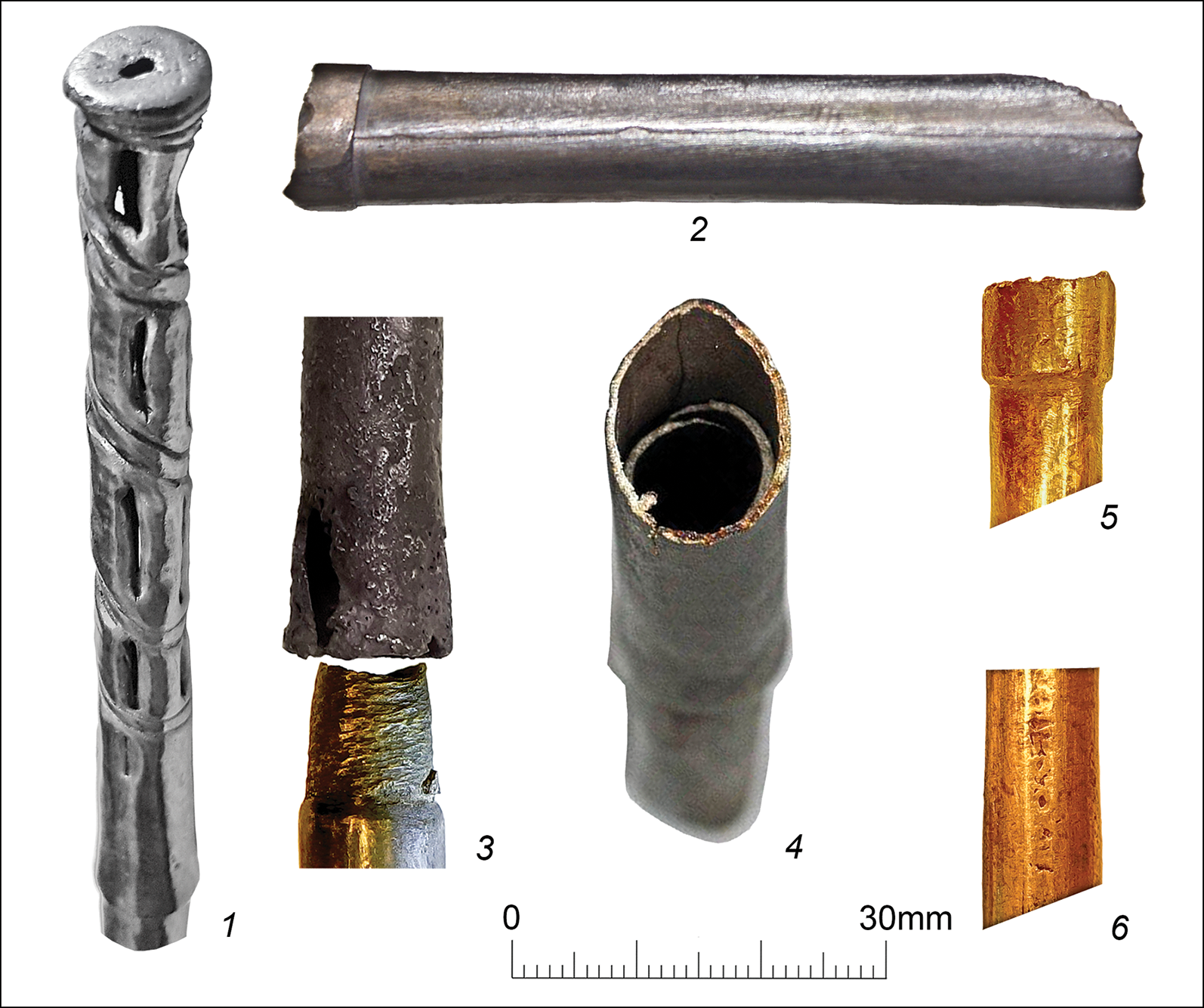

Yet among these trappings of bronze age splendor one group of objects has proven uniquely vexing: a set of gold and silver rods identified by the kurgan’s discoverer, Nikolai Veselovsky, as “scepters.” Long and thin, the hollow rods featured elaborate, bull-themed decoration and pointed tips, which later scholars hypothesized were used to hold up decorative canopies.

New research from scholars at the Russian Academy of Sciences and St. Petersburg State University has re-examined the rods and come to an altogether different conclusion that addresses a number of unresolved questions about their purpose, from their hollow design to their orientation within the grave. These researchers, who published their findings in the British archeology journal Antiquity, instead propose that the rods were used as filtering straws for the communal consumption of beer.

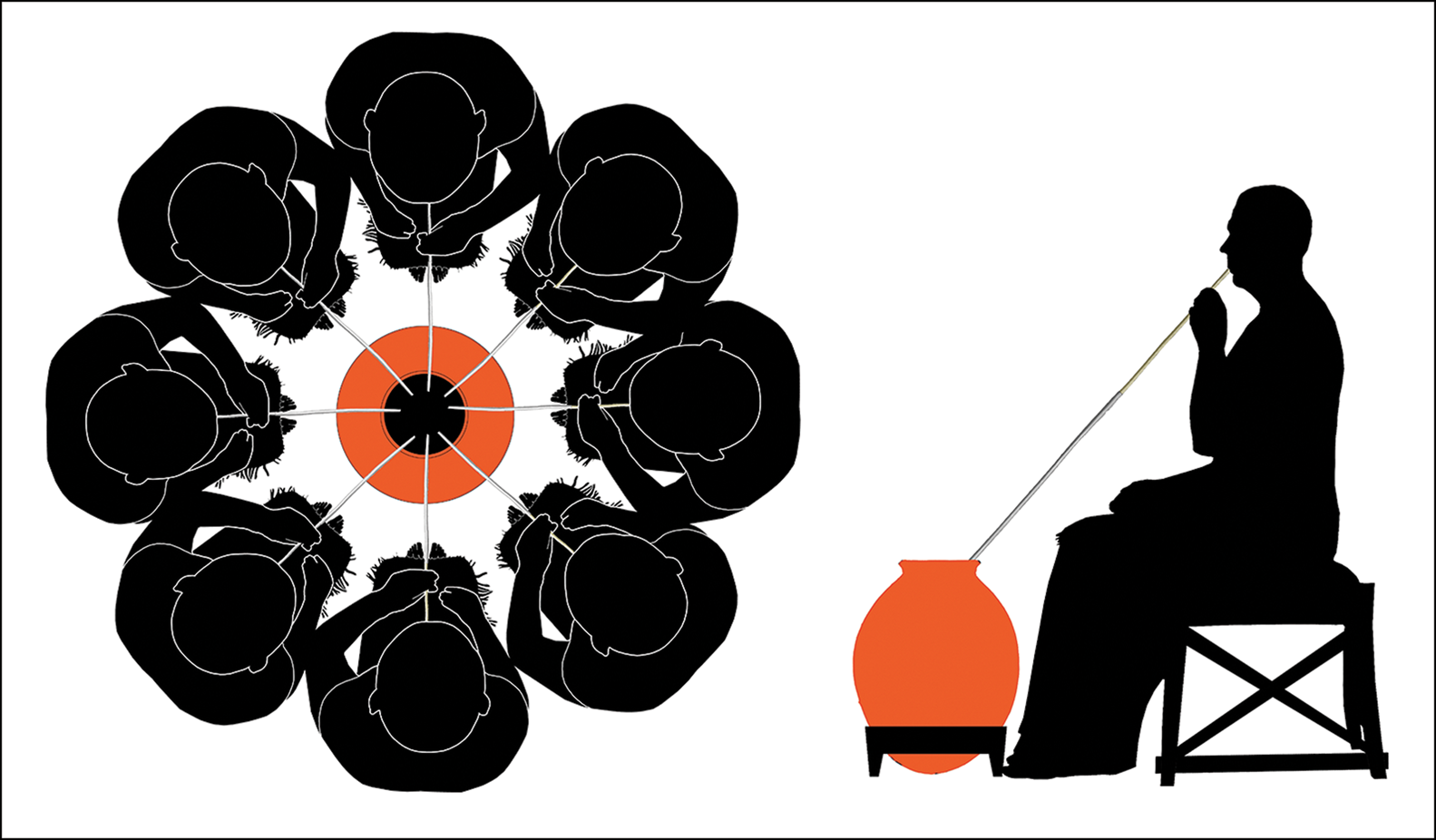

Their findings are based on evidence drawn from other archeological sites, experiments, and microscopic analysis of residue found in the rods. Mesopotamian artwork discovered at sites throughout the region from this period frequently depict communal drinking using long straws to draw from shared vessels, and certain sites, like Queen Puabi's grave in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, feature drinking tubes consisting of long reeds covered in gold foil. In practice, the reed tubes proved easy to prepare, with the paper noting that construction took approximately 20 minutes. Finally, analysis of residue left behind on these 5000 year-old metal rods reveals evidence of barley starch granules and cereal phytoliths, rigid silica structures left behind after the decay of plant tissues. While the researchers note that there is no positive evidence of the presence of a fermented beverage associated with the kurgan, it’s plausible that these tubes were used to filter out the impurities in a barley beer.

These findings not only underscore the long history of ceremonial consumption of alcoholic beverages, but reveal the connections between different parts of ancient West Asia. The rods, our earliest documented evidence of drinking tubes, indicate a common cultural context and trade bonds between the peoples of the Caucuses and the city-states of Mesopotamia — a common cultural context that included drinking together.