At 11:47 PM on 25 July 01978, a baby girl was born at a hospital in Oldham, England. She was delivered via cesarean section and weighed five pounds, twelve ounces. A perfectly ordinary birth, save for one extraordinary detail that would herald a breakthrough in modern medicine: the baby, Louise Brown, was conceived in a petri dish.

“I wanted to find out exactly who was in charge, whether it was God himself or whether it was scientists in the laboratory,” recalled Robert G. Edwards, the physiologist who co-developed the technique of in vitro fertilization (IVF) that made Louise’s birth, and the births of 8 million people after her, myself included, possible. “It was us.”

In the decades since IVF technology was first pioneered, more and more have gained access to its potential for control over life. As our technology has advanced, so too have the ambitions of scientists and engineers. Instead of merely creating life, technologists increasingly aim to use genetic engineering to shape its future. But are these visions of omnipotent control over reproduction accompanied by an ethical frame worthy of their deep consequences? And who, ultimately, will have access to it?

The miracles of modern medicine come at a steep cost. IVF is publicly funded in countries such as New Zealand and Canada, but in the United States, it's an industry on the frontier of laissez-faire capitalism.

The average cycle costs between $10,000 and $15,000, making it a lucrative niche for investors and privatized clinics. While analysts expect the market for fertility treatments to reach $41 billion by 02026, infertility remains a limited business.

As the battle for market share heats up between pink-infused boutiques and national chains, reproduction becomes commercialized. Fertility experts sell expensive dreams through false hope, branding themselves as “baby whisperers” or “IVF magicians” or “miracle doctors.” Wellness companies capitalize off biological clock fears. Specialist clinics employ upsell tactics, bundle packs and baby-or-your-money-back deals.

Premium procedures — such as Orchid Bioscience’s preimplantation genetic and polygenic screening packages, which start at $6,000 — are often based on flimsy science. But for parents-to-to-be with deep pockets, add-ons that could “protect your future child from genetic risks” are seen as just too good to pass up. Bridge Clinic takes it one step further, tempting customers with a multi-generational offer: “What if you could help ensure the health of not only your child, but your grandchildren and many generations to follow?”

When it comes to unregulated fertility treatments, Dr. Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, says promises of success are “bogus.”

“There’s no guarantees to what these fertility programs are suggesting," he tells me. "IVF is one of the few technologies in healthcare that have come forward as a business without adequate evidence.”

With certain players racking up a poor track record of questionable ethics and technology outpacing regulation, neologisms like “designer babies”and “catalog babies” have gone mainstream. As have fears of a Gattaca-like future.

Research found that 80% of Americans oppose the use of reproductive technology for non-health reasons. Norm violators such as He Jiankui, who altered the genes of twin girls to be HIV resistant, are met with international backlash.

According to Caplan, the resistance and outrage towards “designer babies” is valid. After all, we’re only at the beginning of a messy and divisive new era of reproduction.

Caplan predicts that, in less than 20 years, subsets of existing technology will tempt the privileged towards greater reproductive control, allowing people to cherry-pick and even manipulate embryos for more “desirable” traits: height, eye color, intelligence, hair. “Designer babies” will be justified in the same vein as cosmetic surgery or private school education, with parents leaning on Western liberal ethics to defend against criticism, demanding respect for capable, autonomous decisions, even when inconsistent with the beliefs of others.

Now is the time to adequately resist and regulate, says Caplan, or else welcome a series of double-edged scenarios.

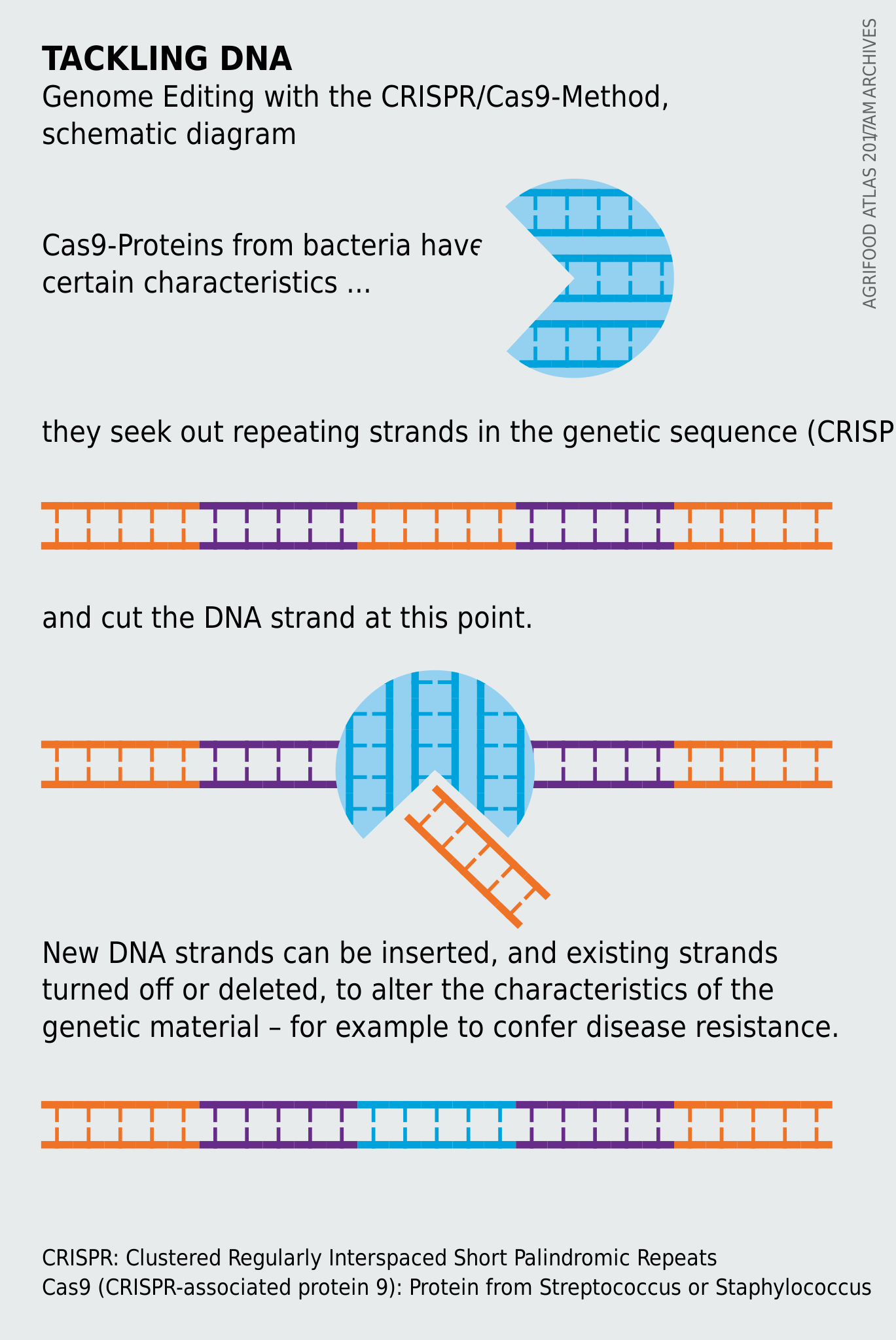

CRISPR/Cas9 gene therapy — a promising genetic editing technique that allows for precise and efficient modification of living genomes — could save lives, reduce strain on the healthcare system and ultimately ameliorate disease in the future. But a tool intended to improve public health may easily be subverted into a system of discrimination. Caplan dreads CRISPR’s potential to fast-track social darwinism and build a future where abnormality and difference becomes less valuable, less than human, less deserving of life. Eradication of “disease” may then include the eradication of so-called “disadvantages” in height, hearing, or sight.

Governments will depend on technology for a smarter, healthier, stronger society. Leaders — regardless of nobility of intent — will interfere with the reproductive process, engineering people to solve whatever problems they created, ignored or inherited.

“Engineering smarter people with better brain power to solve social problems may not be wrong for the ‘collective good,’” says Caplan. “But it will be high stress for the people engineered to do these things.”

Conception sans reproductive assisted technologies could be condemned as a reckless gamble on a child’s life. The “naturally” conceived may file — and win — wrongful life lawsuits against parents who chose to “roll the dice.” It may soon be seen as ethically negligent to refuse genetic engineering for children, in a similar vein to refusing childhood immunization.

In his work, Caplan leans on the four clusters of moral principles outlined by Beauchamp and Childress’ Principles of Biomedical Ethics — autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice — to deal with such dilemmas.

He urges us to consider the children of 02045 forced into positions and responsibilities they may not wish to fulfill, the prescribed scientists who want nothing more than to be a harpist, a poet, or a high jumper.

According to futurist Bruce McCabe, dystopian fear must not blind us to the opportunity of future technologies such as protecting people against sickle cell diseases, cancer, dementia.

This is easier said than done. Humans are repeat offenders at demonizing technology.

In Innovation and Its Enemies: Why People Resist New Technologies, Professor Calestous Juma, an advocate for sustainable development, tracks 600 years of perceived threats to humanity: humans once feared coffee (“the devil's drink”), refrigeration (“the devil’s instrument”), and frozen food (“embalmed food”).

Resistance, argues Juma, is driven more by the fear of loss — to human nature and sense of purpose — rather than a fear of the new.

Humankind will stave off technological threats to our own existence, McCabe believes, on account of one biological mainstay: our survival instinct.

“People will see germline engineering coming into conflict with our survival as a species, and it won’t be pretty,” McCabe says. “There will be widespread revulsion, a counter movement, even people going to war to stop it.”

While he holds that our biological makeup will rebel before a full Orwellian dystopia is realized, McCabe agrees the future of IVF is fraught with risk.

“Don’t ever think that the future will be binary, and that it’ll be all good or all be dystopian. It will be messy,” he warns. “Germline engineering and gene editing will wreak havoc on a localized level, impacting hundreds of children at times. But it will not lead to the emergence of a super species, or transhumanism.”

Still, we should expect some to be blinded to these long-term consequences. The powerful elite may be unable to resist the temptation of technologies that serve their own interests, warned Professor Stephen Hawking in 02018, fearing the loss of humanity.

“Technology will keep evolving and it will be so powerful that the sky will be the limit, literally," says futurist Gerd Leonhard. "We will be able to connect our brain to the Internet, we will know 50 years ahead of time if we may get cancer or not, and healthcare will be for healthy people, not sick people. Pretty soon we’ll be able to do just about everything. It’s more so now about organizing ourselves and deciding what future we want, not what future we can have.”

Thankfully, humans are naturally predisposed to cooperation. Provided we keep a generous stock of optimism, and amplify a cautious narrative of human ingenuity and resilience, we should be able to strike a balance between social order and innovation; between preparing for the inevitable consequences while embracing the many lives created, saved or improved.