In December 02019, a group of scientists from the University of São Paulo, in partnership with diagnostic medicine company Dasa and cloud computing platform Google Cloud, launched DNA do Brasil (DNA of Brazil), a project that aims to trace the country's genetic roots through mass genetic sequencing. Among the project’s main objectives is to create a genomic database of the Brazilian population that can help in the production of medicines and in the research of complex diseases. Led by geneticist Lygia da Veiga Pereira, the project has already analyzed thousands of genomes and sequenced 2,100 with funds to reach 4,400. Their ambitions are more expansive: they aim to sequence and analyze up to 200,000 genomes.

About 80% of the sequenced genomes in the world come from white people of European or North American origin, notes Pereira. In practice, this means that studies that rely on pre-existing genetic databases may not fully capture the world’s genetic diversity. In turn, the diagnostic tests derived from these studies — and future therapies targeting specific genes — may not be as effective on all population groups. The long-standing racial imbalances in access to medical treatment are thus recapitulated into future generations. In very racially-mixed societies like Brazil, where 43% of the population identifies as mixed-race, these imbalances add even more complexity to an already unequal situation.

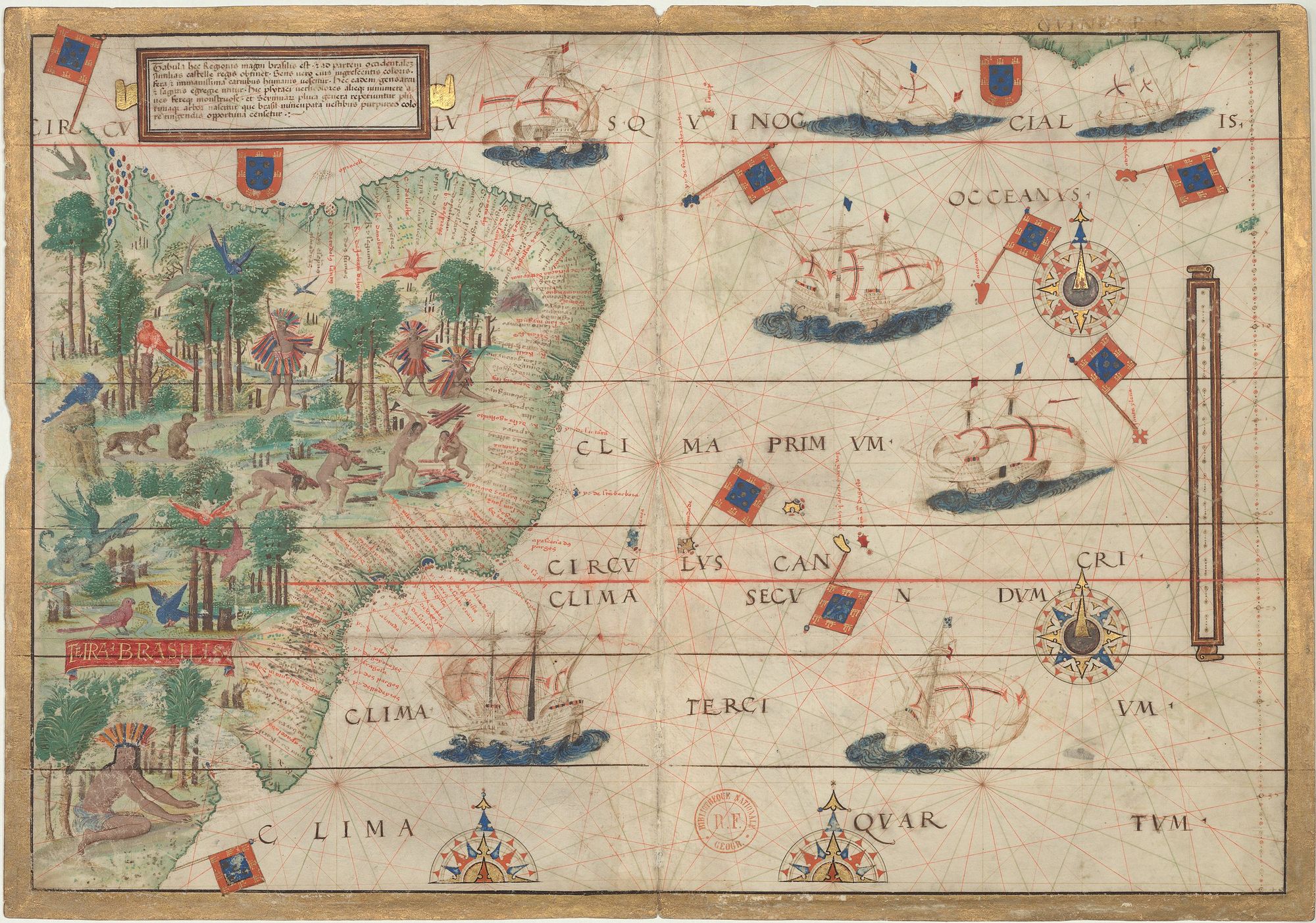

The genomes analyzed by the project so far reveal a disproportionate European contribution to certain portions of Brazil’s gene pool when compared to the indigenous and African contribution — describing, in effect, a history of violence in the formation of the Brazilian nation. During the colonization of Brazil, starting in 01500, Portuguese imperial governments used forced labor — first of Brazil’s indigenous people violently captured by Portuguese bandeirantes, and then of African slaves imported from across the Atlantic — to build an economy based around sugar plantations and precious metal mines with harsh, often-deadly conditions.

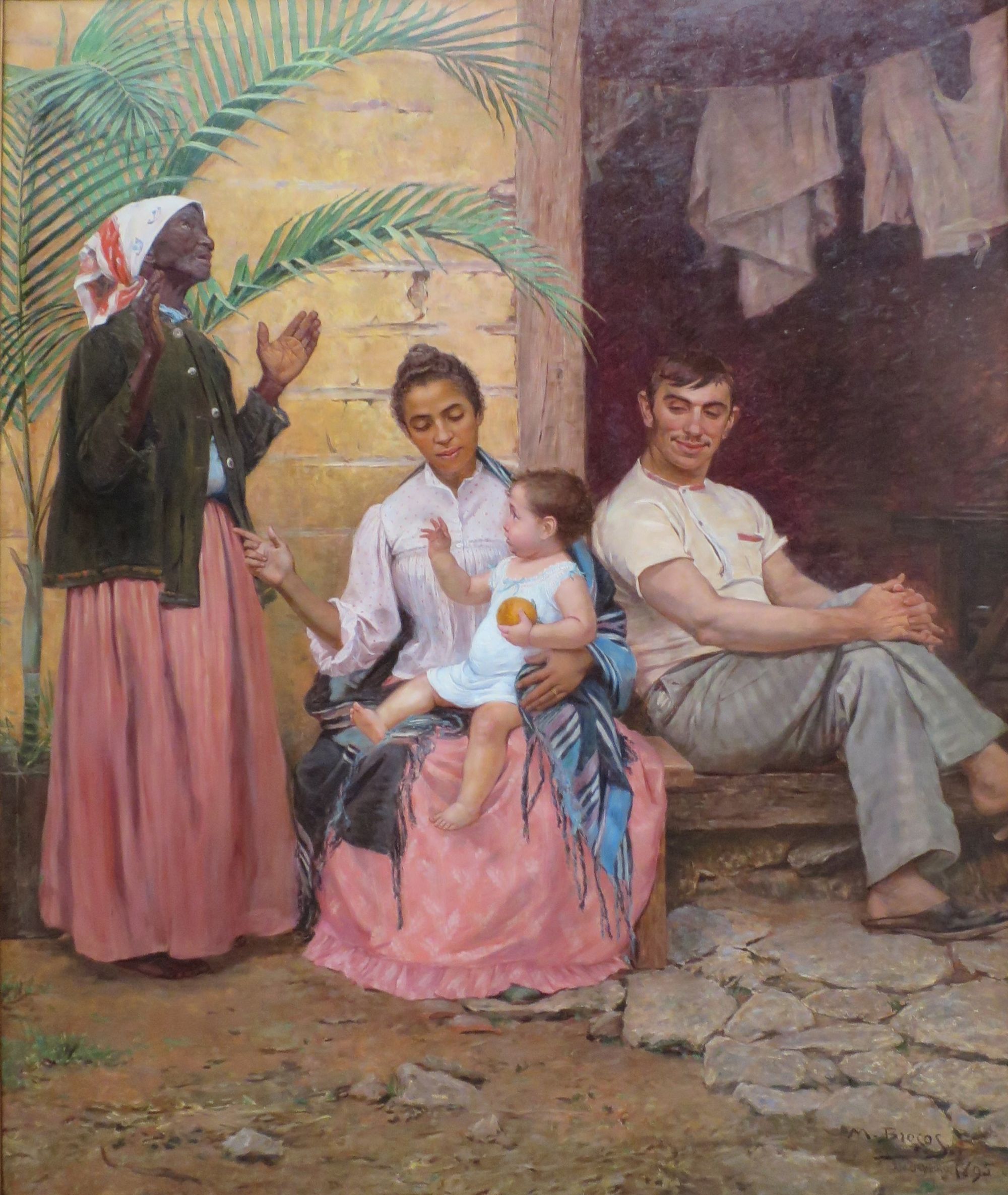

Even after the decline of these industries, slave labor was central to Brazilian domestic life, and Brazilian-born slaves and freed Black people, often the product of a white father and an enslaved Black mother, became an increasing part of Brazilian society. To Tábita Hünemeier, biologist and geneticist at the Biosciences Institute of the University of São Paulo who’s also a member of the DNA do Brasil research group, “the scars of Brazil’s colonization process are too deep to be forgotten” and are indeed embedded in the population’s DNA.

A few studies focused on the US have used 23andMe data to trace Black and Latino ancestry through genomic analysis. DNA do Brasil, however, is the most comprehensive study of its kind in Brazil and all of Latin America. Some of its unique findings help shed light on Brazil’s past. Yet the most powerful impacts of the study may be those that look towards the future, using science and technology to challenge established mainstream narratives and bring focus to the peripheries and those excluded throughout history. By understanding the past, and in this case the collective past of an entire nation, it’s possible to formulate policies to improve the lives of citizens, particularly minorities, and create a better future for all.

“Deep down, this myth still guides us.”

DNA do Brasil is more than a simple research initiative aimed at creating a Brazilian database of genomes as an idle scientific concern; it is a thread through which many Brazilians will learn more about the country's violent past and the complicated process of forming their identities. Through the genetic insights of the project, the Brazilian public may finally be able to grapple with a history of romanticization of the immense violence and brutality of 400 years of slavery, genocide of entire indigenous populations, rape, and inequality.

A persistent myth in the formation of Brazilian identity is the idea of 'racial democracy': that is, that Blacks, indigenous peoples, and white Europeans have mixed freely since the early 01530s, when Brazil was first divided into colonial ‘captaincies’ by the Portuguese crown. This myth has been disputed by sociologists, historians, and anthropologists for many years. Now, DNA do Brasil is mounting a distinct challenge to the country’s civic mythmaking, showing with scientific precision that the formation of Brazil was much more violent and complicated.

This challenge involves revisiting some of the cruelest episodes in the history of Brazilian colonization and slavery to expose the racial machinery behind them. As an example, Hilário Ferreira, a social scientist and historian at Centro Universitário Ateneu, explains that “in old newspapers it was possible to find advertisements offering rewards to those returning white slaves who ran away. Slavery was related to the womb, so if the child was white, it meant that the slave owner’s relationship with the slave was most of the times due to rape.”

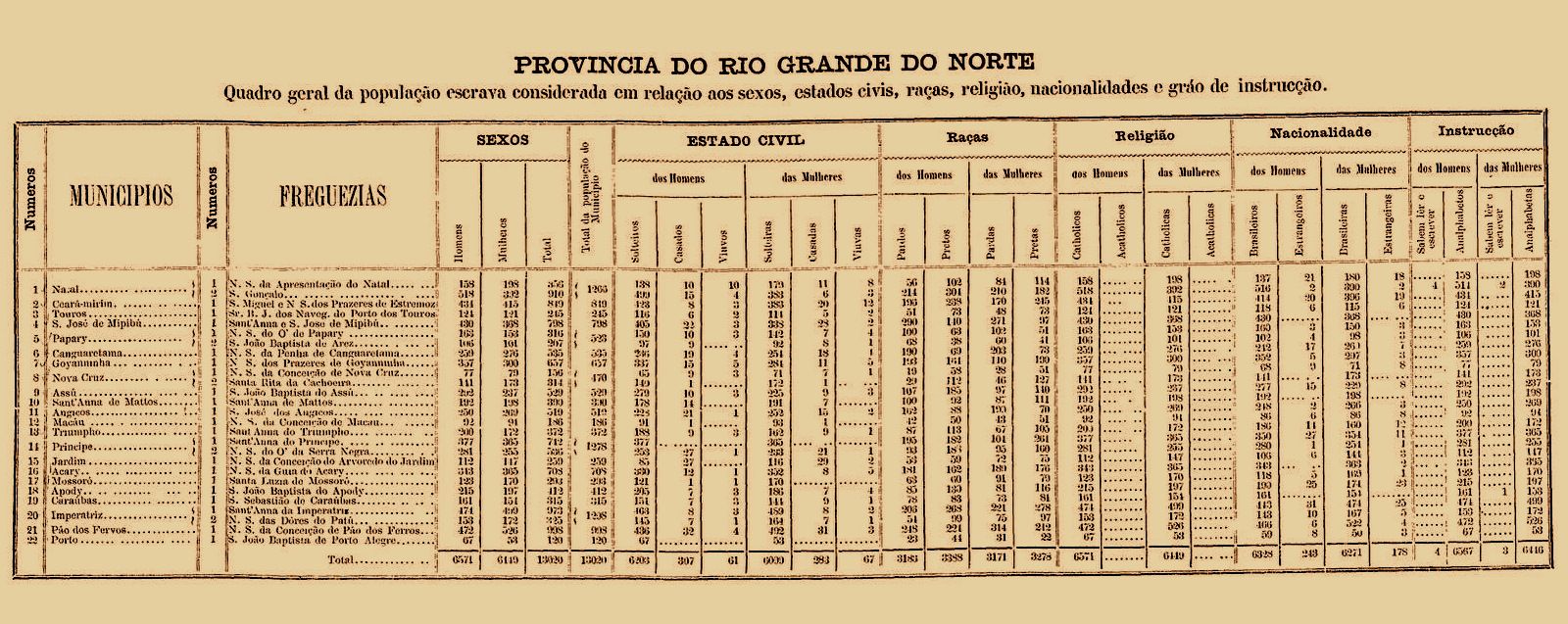

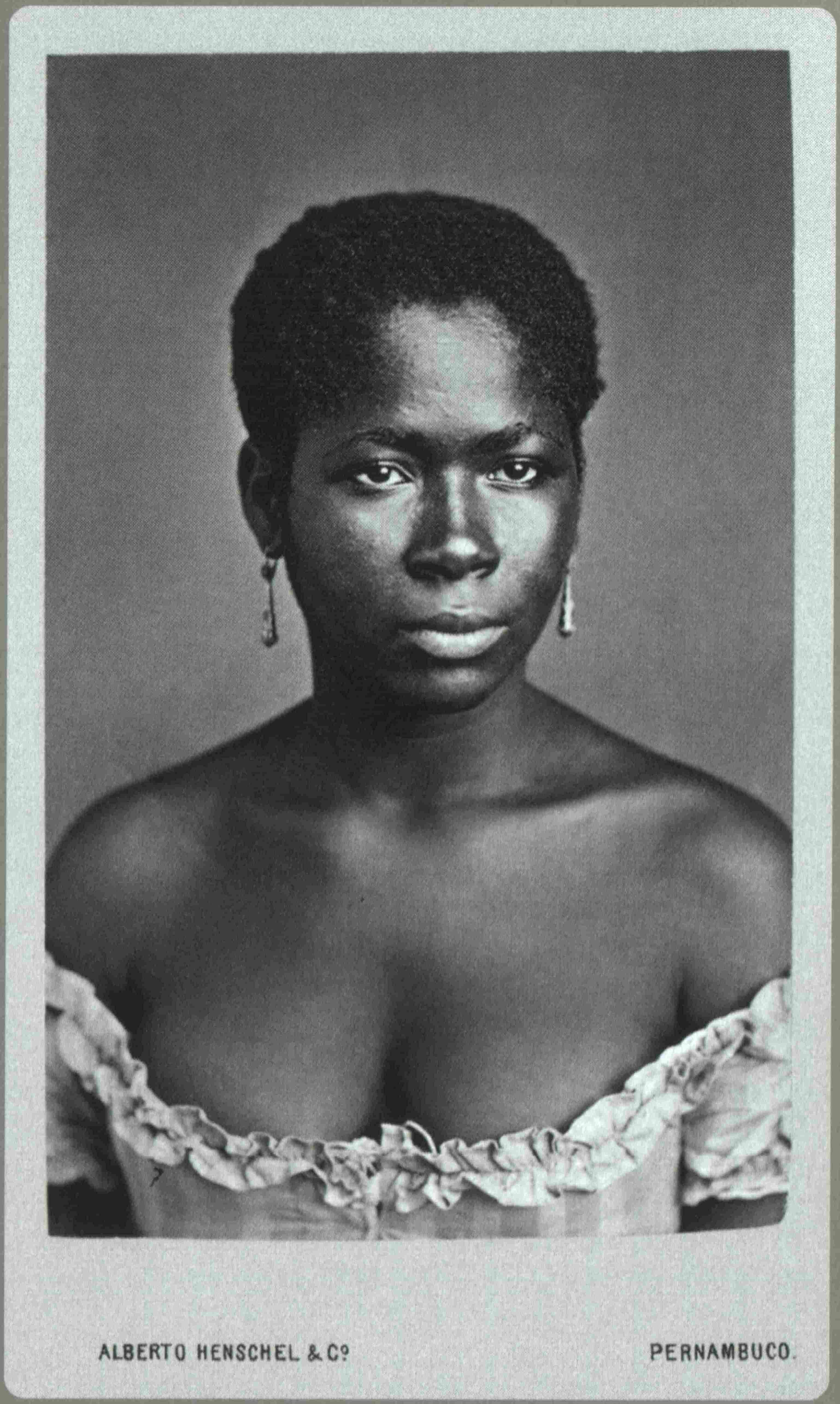

These pieces of historical evidence are supported by tell-tale genetic markers indicating an imbalance in the ancestry of many Brazilians. For DNA do Brasil, the researchers analyzed both the ancestry of mitochondrial DNA (which tracks maternal inheritance) and Y chromosome (which does the same for paternal inheritance) and found that 75% of the paternal Y chromosome inheritance is of European and white origin, while only 14% of mitochondrial DNA, and thus maternal inheritance, is of European origin. Further, 36% of inherited mitochondrial DNA is African and 34% indigenous. Only 1% of the Y chromosome ancestry comes from indigenous men.

Put another way, European men occupy an outsize share of the Brazilian gene pool relative to both European women and Black/Indigenous men. While the presence of genetic markers connected to European heritage within the broader mixed Brazilian population can be explained through a natural process of intermarriage and other peaceful racial mixing, the greater proportion of European Y-chromosomal markers in the overall pool relative to the presence of European mitochondrial DNA markers indicates what the historical record already shows: Brazilian slavery was a system of rampant sexual exploitation and violence.

“Although the Black movements have always confronted the fantasy of racial democracy and denounced racism in Brazil, this narrative is still very strong and present among us,” says Andréa Franco, a PhD candidate in sociology at the Federal University of Paraíba who studies racial relations and Black feminist thought. “This is why the results of the survey were received with such surprise by so many sectors of society, even among people who recognize Brazilian racism. Because, deep down, this myth still guides us.”

Franco, a self-described "Black woman born into a family made up of interracial relations," is one of several Black researchers and activists interviewed for this story who were not surprised by the study’s findings. “The Brazilian population has gone through an intense process of miscegenation,” she says. “And this process has occurred in an asymmetrical way.”

Over the course of Portuguese colonization of Brazil and the subsequent oppressive regimes, both Portuguese and Brazilian, that have ruled over the country, millions of indigenous people have been killed in massacres that lasted from the 01500s into the 01960s and the present day, with many ethnic groups disappearing completely. Today, there are just over 800,000 of them left in a country of more than 200 million, many living in reservations, others in cities, constantly struggling to preserve their customs and traditions.

Part of the colonization process also took place through the slave trade. Millions of Black people were brought from Africa for centuries and enslaved until complete abolition, signed into law on 13 May 01888. The scars of this period remain extremely current, both in Brazilian social and economic inequality — with a majority of Blacks still subjected to violence, prejudice and exclusion — and, as the study points out, indicated in the population's DNA.

After the abolition of slavery until the 01940s, invited thousands of immigrants exclusively from Europe to settle in the country. Decree 528, passed by the Brazilian Republic’s Provisional Government on June 28, 01890, just two years after the final abolition of slavery, legalized and encouraged immigration from all peoples “exceptuados os indigenas da Asia, ou da Africa” [except those indigenous to Asia or to Africa.] In effect, this law implemented in Brazil an official policy of whitening the population. This demographic white-washing of the population via immigration restrictions was coupled with a more tacit whitewashing of Brazilian history. “Brazil had a policy of forgetting there was slavery, even if 70% of the population descended from these individuals,” Hünemeier says.

Piecing Together A Fragmented History

A few years ago, with the popularization of home DNA tests, more people were able to trace their genetic ancestry and learn more about their past. Some results seemed so surprising that they caught the media’s attention, as was the case with the singer Neguinho da Beija Flor, whose Black identity was core to his stage name— Neguinho literally means “little Black.” Yet Neguinho discovered in 02007 that 67.1% of his genes are of European origin and only 31.5% from Africa.

In 02013, data scientist Marco Gomes wrote a long post on his blog about his experience with the 23andMe service. When I contacted him to discuss DNA do Brasil’s findings, he immediately made it clear that he was not surprised by the results of the research. “Black women, the victims of violence, have been complaining about it for many centuries,” he wrote. Yet for many Brazilians, these testimonies were not enough — it was necessary “to wait for genetic studies: 100, 150, 300 years of evolution of science” in order to verify a long chain of history.

The research relates to Gomes' own life: His mother is white, and his father is Black. He said that "it is even difficult to comment" on the process of erasing Black people and the historical violence they have suffered.

The consequences of the attempt at erasure and whitewashing of Brazil’s history and population are still with us today. Franco, the PhD candidate in sociology at the Federal University of Paraíba, tells me that when she sought out the origins of her family, she found plenty of material on the European-white side, but only barriers and uncertainties when researching her Black roots.

Franco explains that she has a white grandmother who came from Portugal to Brazil in the beginning of the 20th century. It was relatively easy to find information about this side of her family. But “as for my Black origins, I need to access their stories in another way. There are no records, no papers. There is memory, loose threads that we sew in conversations with the elders.”

She recalls that “one of my maternal great-grandfathers, it is said, was the son of a landowner and slave owner of a well-known, traditional and important family from Minas Gerais, who had a son with a Black woman (probably a slave woman) and who gave him his surname.”

Franco says that “the desire to know my ancestry by DNA was replaced by the curiosity to gradually reconstruct this story.” She already knows the name of the slave owner, and that “in the middle of the 19th century he had a white wife, 200 slaves from the regions that today are Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and that among these slaves inventoried, only one was registered by name.”

Emilio Moreno, a journalist from the state of Ceará, says that while his Black friends were not surprised by the DNA do Brasil findings, many white journalists were. Moreno’s own heritage is involved in this complex debate.

"Until recently I did not see myself completely Black, because I am lighter-skinned. Only by reading, I was able to understand myself better".

Moreno tells me that he comes from a poor family from the countryside of Ceará and that "we have little record of our origins, we were a farming family and were extremely poor.”

Moreno notes, much as Franco did, that “there is no way to investigate, because it is very common in Brazil that people of Black origin cannot make the connections, unlike those who have a family that comes from Europe, who know the whole origin of their family; we cannot do this research.” The disregard paid to Black Brazilians for centuries is reflected back in their absence from the archives.

The potential result of the research, explains Anna Claudia Evangelista, a medical geneticist and Black woman, "is yet another confirmation – this time through the molecular tool – of the history and the way in which Brazilian colonization took place."

In her medical practice, working in an oncogenetics clinic, "it is very important to ask about family history and ancestry. It is not uncommon for patients to say that their grandmother or great-grandmother, who was an enslaved Black or indigenous, was 'lassoed' by an immigrant of European origin."

Journalist Carlos Alberto Ferreira is one of those who has in his family stories of women who were "lassoed,” and his mother “lived with a grandfather who was enslaved and may have been begotten of a rape.”

He explains that he did two DNA tests (Genera and My Heritage) and "both served to prove several old stories in my family.”

His family story is one quite common in Brazil. He grew up in a very multiracial family, with white, lighter skinned Black and dark skinned Black people all intermixed. “I remember people not believing me and my cousins belonged to the same family because I was Black and some of them white.”

He continues by saying that “I can clearly see that the lighter-skinned part of my family has had access to better education, lives in better neighborhoods and has progressed better in life. On the other hand, the part of the family with darker skin have not completed higher education, live in more peripheral neighborhoods and have a lower quality of life. It's subtle, it's not spoken about, but it exists and it's open. Racism in Brazil is inside the house with people hiding it with shame, even if it is with the same DNA.”

The role of the new studies into Brazil’s DNA is key here. Scientific research can shed light on what Black people have always known and felt.

An Incorrigible Optimism

DNA do Brasil offers more than just a reconsideration of national and personal histories. Beyond everything else, the findings of the study are providing a wealth of scientific knowledge that could lead to groundbreaking practical uses.

Pereira explains, without hiding the excitement, that "we are already seeing that by sequencing the genome of Brazilians we find a number of variants of unidentified sequences not yet found in other populations." These findings, according to Pereira, are “very significant” for a variety of reasons.

Besides the "enormous opportunity for us to get to know new genomic variants associated with phenotypic and genomic characteristics, we are also seeing the ancestry of an American population that no longer exists,” explains Pereira. “Sequences of extinct populations and mixture of African ancestry – we find mixtures of African populations that we don't even find in Africa, but that are found in Brazil.”

Hünemeier jumps in, saying that she’s “thinking of the number of indigenous people we had here, about 3 million, and this African contingent forced to come to Brazil," both with vast genetic and linguistic diversity. She notes that "We can map this out by working at the genomic level. And also, many Europeans, from various parts, with diverse histories – as fugitives, for example. There is all this mosaic represented in Brazil, with the largest Black population outside of Africa and, for the first time, we have included indigenous people in genomic studies.”

For those of African descent, the research sheds light on their past. If in many cases it does not bring surprising news, it does give them a tool with which they might change Brazil's racist mentality little by little. Moreno explains to me that this research "ends up being yet another indicator that the country structures its racism to maintain the privilege of white people and of those who have a more comfortable place [in society]. So perhaps I can tell you, from my incorrigible optimism, that it helps whites understand how they are part of this structural racism.” For those long left out of the upper echelons of Brazilian society, they can now hope to tell the story as it really happened, rather than the institutionally supported narrative that denies centuries of genocide, violence, and attempts to erase the country’s Black history.