Something strange is happening on TikTok. In one video, a white candle labeled “Her” and a black candle labeled “Him” are tied together with rope. They burn simultaneously until the rope catches fire, dropping between the candles and igniting the remaining length of the black candle. Another video shows a woman with bright green hair telling you to turn your broom upside down to make someone unwanted leave your home, or to put cinnamon sticks on top of your doorframe to bring abundance to your life. In yet another a woman sits on an armchair with a spoon spinning in her cup of tea while her hand makes circles in the air without touching the spoon. This is just a small sample of what you can find on WitchTok, an online community of witchcraft practitioners. It’s not fringe, either: the #witch and #WitchTok hashtags have tens of billions of views — more than #kimkardashian, #beyonce, and #donaldtrump. WitchTok provides a supportive group that Raven the Witch, a community member, describes as a place where “Everyone can be a witch, and every witch is beautiful.”

When most people think of “witches”, images of witch trials and innocent women burning at the stake come to mind. For centuries, witches were seen as evil, associated with the devil, prosecuted, and killed in the thousands. So how did the cultural meaning of witches change so significantly, enough that a generation of young witches could take over the internet?

To answer this question we must examine the history of witchcraft and the use of the word “witch.” In doing so, we’ll see how the seeds of today's WitchTok community were sown back in the 01960s, when a group of people known as Wiccans set out to revive what they perceived as an ancient witchcraft religion. In doing so, the Wiccans set in motion a process of reclaiming a term of oppression and giving it a new life, allowing the modern-day witches of WitchTok to build a positive and welcoming spiritual community.

“These Detestable Slaves of the Devil”

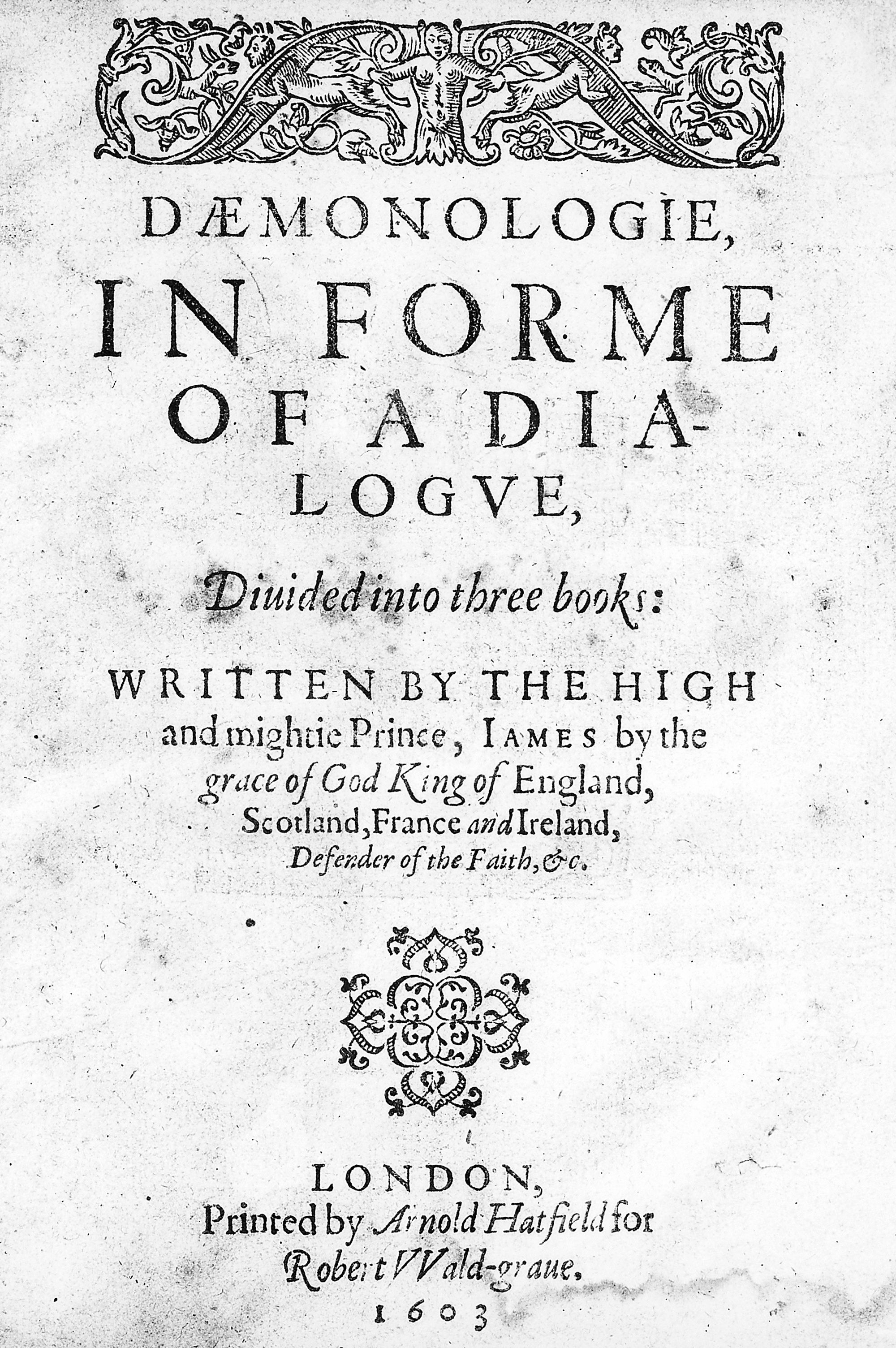

Historically, witches were viewed with paranoia and hostility. During the reign of King James VI and I over England and Scotland in the early 01600s, witchcraft hysteria was reaching a peak in Europe. The King even penned his own Daemonologie, published in 01597, featuring dire warnings:

“The fearefull aboundinge at this time in this countrie, of these detestable slaues of the Deuill, the Witches or enchaunters, hath moved me … to resolue the doubting harts of many; both that such assaultes of Sathan are most certainly practized, & that the instrumentes thereof, merits most severly to be punished…”

Punishment was indeed what befell a woman suspected of being a witch in the late medieval and early modern period in Europe and North America. While the well-known Salem Witch Trials took place in the 01690s, European witch-hunting began its rise more than 300 years prior in the late 01300s, occurring mostly throughout France, Germany, and neighboring countries. One particularly infamous trial took place on the morning of October 29th, 01485, during which Helena Scheuberin, the wife of a prominent local merchant, was interrogated in the Austrian town of Innsbruck. After a fervent prosecution by Catholic inquisitor Henry Institoris, laced with accusations of sexual impropriety only tangentially related to witchcraft, the town’s leadership moved to dismiss all charges against Scheuberin. This trial’s failure to convict would go on to inspire Institoris to write one of the most well-known publications of the 15th century: a treatise on the subject of witches, how to identify them, and how to prosecute them. This book was called the Malleus Maleficarum (the “Hammer of Witches”).

From this point until the end of the 01700s, being accused of witchcraft was often a death sentence, with an estimated 60,000 people — mostly women — killed.

Robin Briggs, a historian of Early Modern European History at Oxford’s All Souls College, says that there were more-or-less “two historical definitions” of a witch in the early modern period. In the first instance, a witch was “another person who does you some sort of harm by vaguely occult means, rather than by direct action — there might be some physical contact involved, poison or some sort — but on the whole it’s an inherent power that other people have, propelled by ill-will.” He describes this as a “basic idea that goes back into the mists of time.” The second historical definition was newer, and construed witches as people “organized and somehow directed by the devil, a concept that gets ‘inserted’ around the 15th century [...] by some clerics and lawyers.”

One strong connecting aspect of the witchcraft of the 15th century up until the present day, is that most so-called “witches”, both now and then, are women. Robin Briggs says that many of the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries were based on a superstitious reaction related to “sicknesses of children, and appalling death rates among infants,” because women were most often closely associated with the care of children and elderly, which led to “accusations of witchcraft.”

However, Briggs notes a lack of certainty around why most people targeted by the witch hunts were women, describing it as a “difficult question” and says that there was probably “something in the social organization which tends to stimulate more accusations among women.” He also explains that on another level, it has “to do with beliefs about women, women’s greater emotionality, [and] susceptibility to the devil.”

The era of witch hunts in Europe and North America ended as quickly as it began. Robin Briggs says that people, and particularly the members of the secular courts who tried the vast majority of witch trials, “quickly became suspicious about what was going on.” By the end of the 01620s in France and England it was “extremely difficult to get convicted as a witch.” The practice of witch trials continued for longer in Colonial America, but within two decades of the Salem Witch Trials the prosecution of witchcraft became extremely rare in North America as well. As courts and both clerical and lay professionals began to grapple with the “practical experience of trying individuals as witches” they became disillusioned. In the end, they “learned from experience” and the vast majority of witch hunts stopped.

A Sacred Prehistory

Yet witchcraft would remain a fringe presence in Western society for centuries past the peak of the Malleus Maleficarum’s influence. Only in the second half of the twentieth century would witches begin to venture their way out of the underground. Revitalized in the 01960s and 01970s, Wiccans forged a connection to the persecution of foregoing accused witches, believing that the witch trials had been targeting a so-called “witch-cult”, an early Pagan religion. This “witch-cult” theory was initially proposed by Margaret Murray, an Egyptologist known for her books The Witch Cult in Western Europe (01921) and The God of the Witches (01933). Murray’s views were picked up by retired British Colonial civil servant and part-time occultist Gerald Gardner in his Witchcraft Today (01954) publication, which was widely disseminated and strongly influenced the early establishment of Wicca.

Despite Murray’s views later being disproved as unsupported by historical evidence, modern Wicca practitioners nonetheless saw her ideas as a “sacred mythology, or mythic history.” The early adherents of Wicca continued to “claim that [Wicca] was the survival of this witch-cult and that its lineage stretched back into deep prehistory.” As a consequence, they adopted terminology such as the Old English word “wicca” meaning sorcerer or witch. This term was an initial attempt to distance themselves from some of the negative connotations of the word “witch”, while remaining connected to its history: a process of linguistic shaping that would later lead to its full reclamation in contemporary groups.

The rise of Wicca in the 01960s and 01970s developed alongside other counterculture changes such as the feminist, anti-war, and environmental movements. Helen Berger, Professor Emerita of Sociology, West Chester University of Pennsylvania, says that Wiccans attempted to use ideology that connected to the “old ways”, as certain older beliefs resonated with counterculture and other New Age mindsets. In particular, Wiccans felt that they were “going back to a connection to nature, to seeing the divine in nature [...]. [They saw things as] having animism, seeing things as alive, in an older worldview in which all things are part of the great chain of being.” Despite Wicca’s disproven link to the past, the ideology resonated with the cultural trends of the time: the New Age movement, Caroline Ball writes, “that was such an integral part of this counterculture, with its renewed interest in mysticism, occultism, arcane traditions and unorthodox spirituality” was part of what allowed Wicca to take root and flourish.

Wicca, Ball notes, has “always been closely connected with the political, not least because many of its followers found their way into Wicca through specifically political movements such as the feminist or environmental movements.” The feminist association with Wicca led to many of the adherents being female. This may have created a dynamic of self-identification as a method of reclaiming the word (albeit slowly) to gain power and control over it.

Even the Wiccans of the 01960s were seen as part of a counterculture — not so strictly persecuted per se, but not particularly accepted either. Much like contemporary LGBTQ+ labels, once-maligned terminology was adopted by Wiccans and contemporary witches through linguistic reclamation: a “process of taking possession of a derogatory label … [through which] stigmatized group members consciously use it to label themselves, thereby turning a hurtful term into a badge of pride.” For witches, this reclamation began in the 01960s, where women in particular reappropriated the word “witch”, taking it from an accusation that could lead to death to a way of self-identifying as part of spiritual, feminist, and community groups.

Re-taking control over a derogatory term such as “witch”, through the associated term of “Wicca” was perhaps also an attempt to reduce oppression against women through its use. The continuing evolution of this linguistic process ties in to the explosion of witchcraft practitioners on WitchTok today: in more recent iterations of the feminist movement the fight has, as journalist Jessica Abrahams has written, “shifted its focus from legal equality to a kind of discrimination that is harder to quantify.” Part of this focus involves a recognition that the words we use, and the ideas we have about women also need to change, not just how much we pay them. Fourth wave feminism recognises that "unconscious stereotypes about women affect how they are perceived and treated”. The reclamation of female identity and its association with witchcraft is likely part of the trend of modern WitchTok users, though this is yet unstudied.

Helen Berger explains that in this respect there has been one major change in the idea of what a witch is. In line with Robin Briggs, she says that witches were historically accused of “cavorting with the devil” but that this is a far cry from “contemporary witches, who don’t believe the devil exists: it’s very hard to cavort with a so-called imaginary friend.” Raven The Witch agrees, noting that “the most well-known misconception of them all is that witchcraft means that we are worshiping Satan, which is definitely not the case.” Self-identified witches have attempted to remove negative semantic associations and to create a new, less oppressive meaning by distancing devil-worship from Wicca and contemporary witchcraft.

The movement of contemporary witchcraft has shifted the ideology even further: on sites like TikTok and Twitter, young people have used the terminology of long-ago persecuted women, and adopted some of the spiritual practices of 01960s Wiccans, to forge a community of witches that is at once a throwback to earlier practitioners and also something entirely new.

“It feels like I’ve finally found my home.”

The #witchtok hashtag on TikTok has over 42 billion views, while the #witch hashtag has over 25 billion. Many of the videos show tarot readings, crystals, candle-burning rituals, and advice for new witches who want to get involved. Some also show videos of covens meeting offline, dancing around fireplaces or singing and chanting. The startling shift from once-persecuted women — first to the “hippie” and New Age Wiccans, and then to WitchTok, is astounding. The word “witch” has taken on an altogether different meaning in the modern day. Raven the Witch describes contemporary witchcraft as “an open spiritual movement where everyone is welcome to join”. She notes that WitchTok is a place “where everyone can find something that fits their needs or interests'', and describes it as an "an amazing community to be a part of.“

For Raven the Witch, calling herself a “witch” was something she only felt she could claim once she had become an expert in some way: “when I discovered that witches were in fact real I started reading the books they published, watching their videos, reading their blog posts, trying out spell recipes, reading tarot and so on until I was confident enough in my own skills to actually start calling myself a witch.” This voluntary self-identification stands in stark contrast to historical perceptions and accusations of witchcraft, and indicates that a noteworthy linguistic and ideological shift has taken place. The idea of a “witch” is no longer negative in young women’s minds, and seems as if it has lost its sting as an accusation. Nor is it part of a large countercultural movement at the center of political outrage or suspicion. Instead, it appears more akin to a hobby group or spiritual community entrenched deeply online as many contemporary interest groups are.

The mostly young and female-presenting members of WitchTok see witchcraft as less attached to political motivations than the Wiccans of the 01960s, although Helen Berger says that WitchTok still seems to have a “girl power” aspect. WitchTok is both a social and cultural movement, with Raven the Witch calling WitchTok “definitely a spiritual movement” as well. She says that “the craft has also become much more gender neutral,” explaining that “the word 'witch' is a gender neutral word itself. So any person, if they identify themselves as he, she, they, them, and so on can still call themselves a witch”, an openness that follows contemporary ideas of gender and inclusion. This approach further distances contemporary witchcraft from historical dynamics of misogyny by opting out of gender binaries and stereotypes altogether.

The numbers of people practicing contemporary witchcraft are unknown, although Helen Berger says that the number of people describing themselves as Wiccans is increasing. A Pew Research Center study conducted in 02018 estimated 1.5 million Wiccans in the U.S., up from 340,000 in 02008. With the numbers of witches sharing videos on TikTok, this may be an accurate read of the trends. While popular and digital forms of witchcraft may be at risk of being seen as a “passing fad” on social media when compared to more traditional forms of witchcraft, Helen Berger sees their practice as “quite serious”. She notes that “what they’re doing is not that different from what other Wiccans and eclectic witches are doing offline, older ones”. Importantly, she says that it is “very easy, and it’s too easy to disregard the young. I am not into that: I think they should be taken seriously.” As for whether the mostly-young TikTok witches will continue their fascination with the movement, or expand its influence beyond the online world, this is yet unknown. A potential backlash may simply be yet to come.

The complete turnaround from derision, suspicion and death befalling witches in the 16th and 17th century, to the political associations of the Wiccan spirituality in the 01960s and 01970s, to the explosion of TikTok users on WitchTok today shows the linguistic and social transformation of the term, and a marked shift in acceptability (for now). A word that was once associated with a death sentence has become a symbol of a community that prides itself on inclusion. The WitchTok community is now a supportive safe-haven for people who want to experiment with witchcraft and its themes: Raven the Witch emphasizes that “it's all about doing the thing that you love, and making the craft your own.” To Raven, WitchTok is a “place where I can be myself, where I fit in and where I can do awesome things. I learn a lot, work with deities — I mean, how cool is that — and meet amazing people along the way.” For her and many others online, WitchTok is a welcoming space: “it feels like I have finally found my home.”