As installation begins at the Texas site for Long Now’s monumental 10,000 Year Clock, it’s worth taking a step back to examine the Clock’s larger artistic context and its place in the history of Land Art in the American West.

Long Now’s staff and many of the individuals working on the project and serving on our board have drawn inspiration for the 10,000 Year Clock, and its placement in the remote landscape of West Texas, from these early Land Artists and their great works. These artists pushed the boundaries of size, materials and time and the cultural norms of their day. In this, the first article in a three-part series, we explore the art and ideas of some of the first group of Land Artists to work in these Western states starting in the 01960s. The other two parts of the series can be read here and here.

The Birth of the Land Art Movement

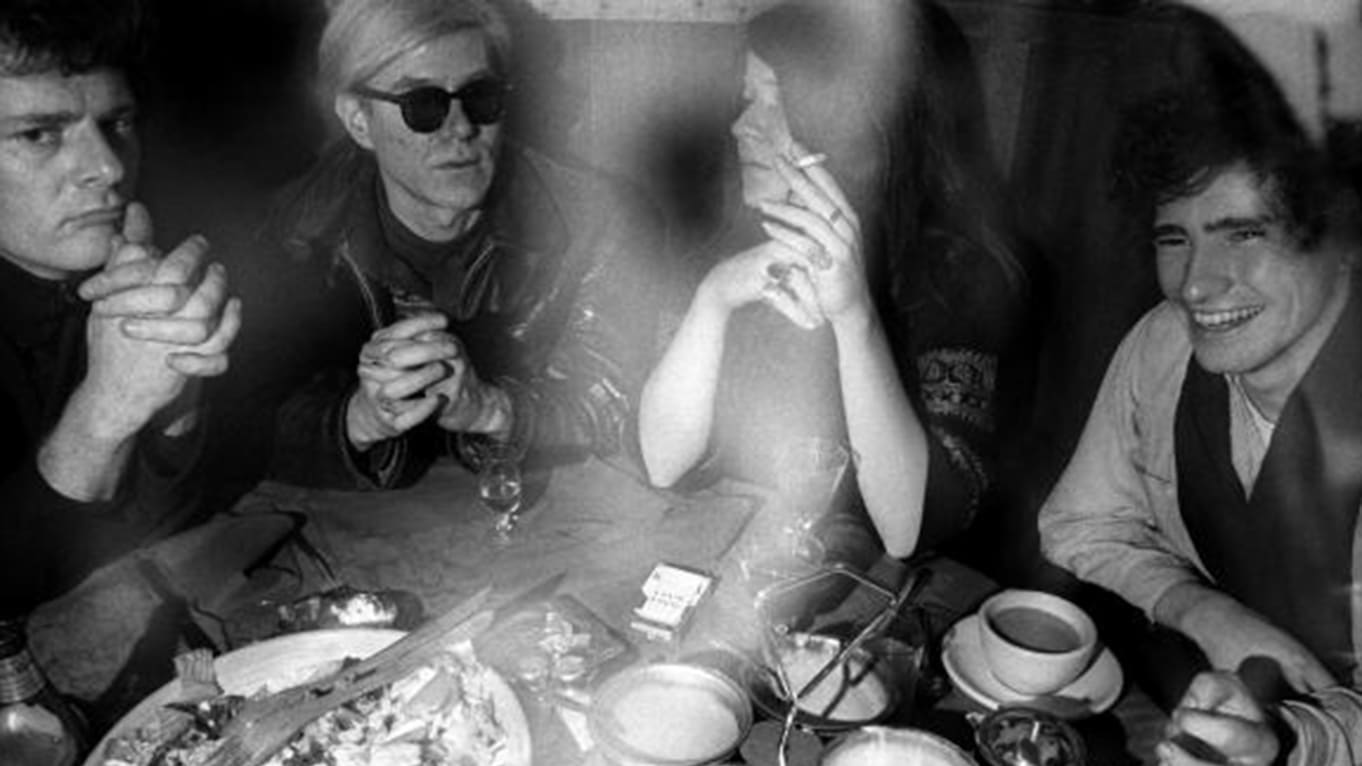

Many of the artists who created the earliest monumental-scale works of art in the American West met in New York City. More specifically, many of them met at Max’s Kansas City, an establishment in Manhattan that was frequented by all sorts of artists, from Andy Warhol to Allen Ginsberg.

It was at Max’s Kansas City that Land Artists-to-be Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson were introduced, and where they regularly met with each other, Walter De Maria, and Nancy Holt. These four artists were among the first to explore the creation of massive works of art using natural materials in the remote landscapes of the western United States. Their artistic motivations and perspectives were various, but they all influenced each other. Their works were often designed — at least in part — to communicate the expansiveness of earth and time. They were also driven by a desire to push the boundaries of the enclosed gallery and Museum spaces they were restricted to in New York and other cities, to create large works of art outdoors, in remote locations, that could not be toured or exhibited—art that you had to intentionally journey to in order to experience fully.

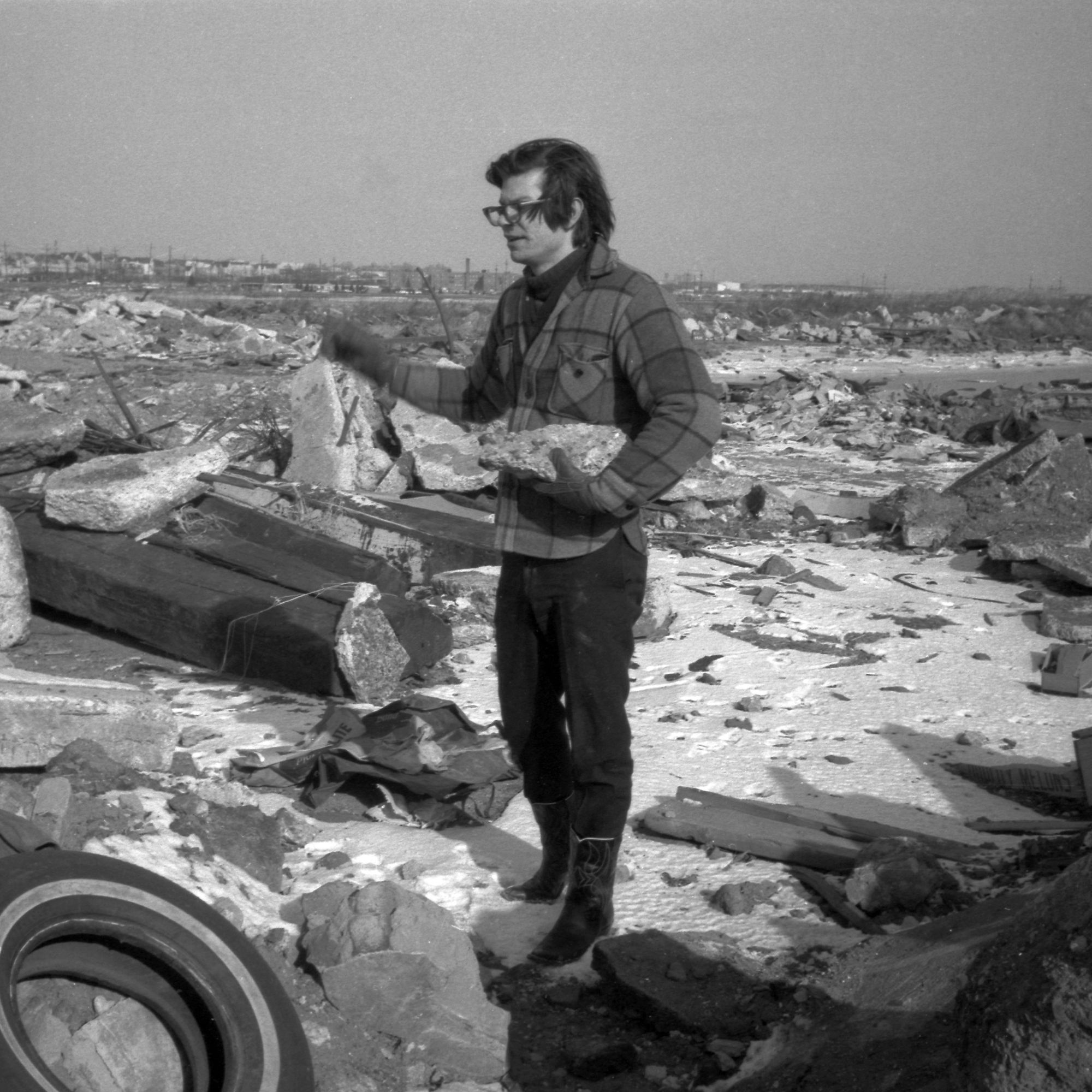

Michael Heizer and Walter De Maria were both originally from the San Francisco Bay Area. Heizer in particular was familiar with the open landscapes of the West — he had a long family history of geologists and archaeologists in Nevada and California. He saw in the Western deserts the physical space to create large scale pieces.

“I’ve made it big to make you feel small standing in it. Flying over it squishes the Gestalt. It’s supposed to be about a motor-delayed, cumulative observation: you’ve got to walk around it, climb over it and later put it together in your mind and figure out where you were. It isn’t the old convenient art object.” —Michael Heizer

Venturing out west from the New York scene was for Heizer an act of returning, rather than exploring new territory, as it would be for some Land Artists. His work in the Sierra Nevada mountains entitled North, South, East, West was, in 01967, a fairly small but clear example of what would come to be known as an Earthwork, and later as Land Art.

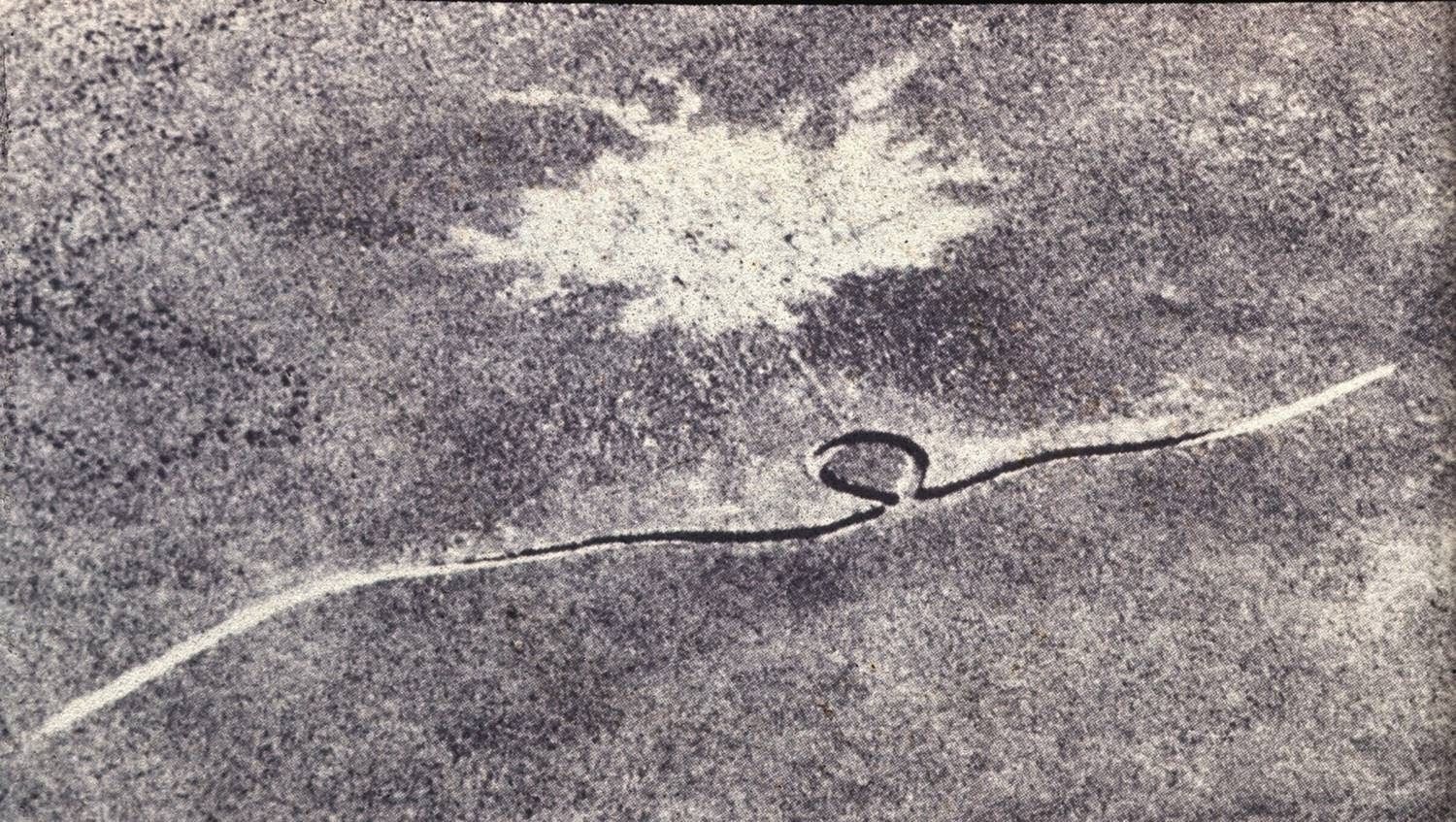

Heizer returned to Nevada in April of 01968 with Walter De Maria. Heizer had been commissioned by art collector Robert Scull (it was De Maria who introduced the two) to create Nine Nevada Depressions — “big, curved and zigzagging trenches, like abstract doodles on the earth, placed intermittently over a span of 520 miles.” De Maria worked on his own project, Mile Long Drawing — two parallel chalk lines in a flat valley of the Mojave desert. These two works of art are both too large to fit in a gallery and too remote for casual visitation — both hallmarks of Land Art.

Partly in response to this enormity and inaccessibility, when Walter De Maria completed Mile Long Drawing he did something that would also become common among works of Land Art: he took pictures of it so that it could be displayed in urban galleries. In one of the photographs, De Maria appears in the landscape, lying on the ground between the two parallel lines. This translation of large outdoor art to indoor art, part reproduction and part co-production, was a tricky sort of dance for which each artist formed their own solution. (Indeed, some Land Artists such as Mary Miss rejected the inaccessibility of remote sites, arguing that such placement was just as undemocratic and distant as the traditional gallery format.)

In the summer of 01968, Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt went out West to visit Heizer, who was still working on Nine Nevada Depressions. Smithson was a prolific writer and prominent voice in New York art scene at the time. In a 01967 article in the journal Artforum he coined the term ‘earth works’ and discussed the aesthetic potential of “pavements, holes, trenches, mounds, heaps, paths, ditches, roads, terraces, etc.” Heizer has repeatedly declared the creative independence of his work from other artists, though he was familiar with Smithson’s writings which corresponded to Heizer’s notions of ‘negative’ sculpture. (Nine Nevada Depressions, like the later Double Negative, are excavations — like the holes and trenches of Smithson’s article.)

During his trip with Heizer and Holt in 01968, Robert Smithson collected rocks around California’s Mono Lake. He shipped them back to his studio in New York to create what he called a ‘nonsite’ piece. The nonsite is part of Smithson’s answer to the problem of sharing remote, monumental and experiential art. Smithson scholar Ann Reynold’s describes the concept this way:

All of his work conforms to this dialectic: the chosen site — New Jersey, the Great Salt Lake, or the Yucatan peninsula, for example — and what he did or made there and what he took from these sites — photographs, drawings, and film footage of his activities, indigenous materials such as sand or rocks, and maps — the nonsite. The two — site and nonsite — are not equivalent or interchangeable. —Ann Reynolds, in Land Arts in the American West (Gilbert & Taylor, 02003)

Some of the nonsite materials that Smithson collected in 01968 were being prepared for a seminal gallery exhibit that took place in October of that year. The show was called “Earth Works,” and took place at the Dwan Gallery in New York.

Virginia Dwan was an adventurous young patron of the arts who knew Smithson, Holt, De Maria and Heizer in addition to other artists starting to work with earth materials. She had been discussing the idea of featuring ‘earth works’ with Smithson and Holt, and since there weren’t any large expanses of affordable land near the gallery, they decided to somehow bring the landscape into the gallery. Among the pieces shown at the exhibit were a nonsite work by Smithson, a 6×6 foot backlit transparency image of one of Heizer’s Nine Nevada Depressions, and an enormous monochrome painting, by Walter De Maria, that was the color of the Caterpillar brand of earth-moving equipment. It was entitled The Color Men Choose When They Attack The Earth.

Soon after the “Earth Works” exhibit Dwan funded several Land Art projects, notably Michael Heizer’s Double Negative and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, both completed in 01970.

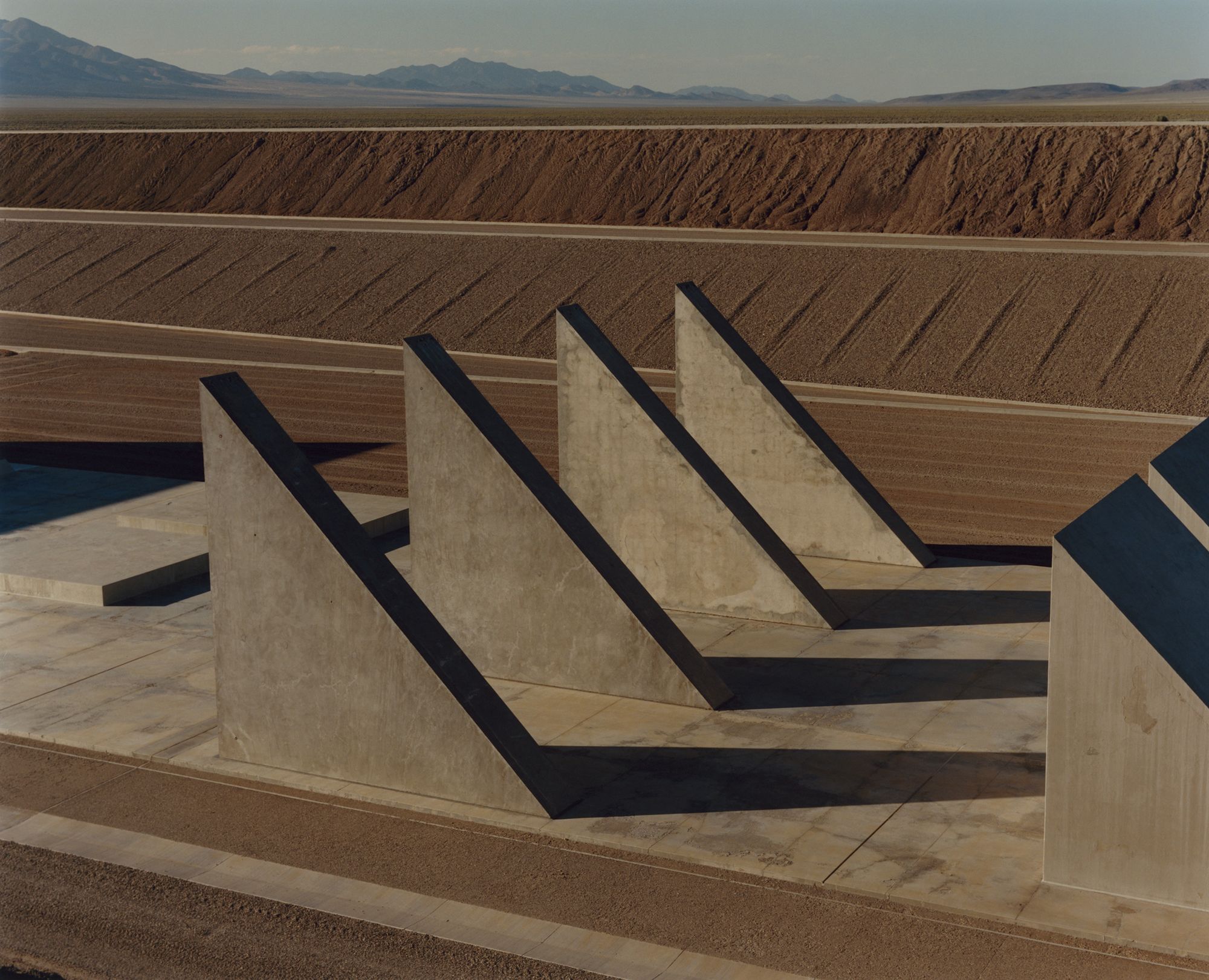

Double Negative is essentially a pair of trenches dug into the sides of a gap in a desert mesa. 240,000 tons of earth were moved into a ravine, leaving long empty spaces that face each other in alignment. It is located near Overton, Nevada — quite far from any large human population — but Dwan and Heizer made an effort to invoke the experience remotely. Dwan described a poster that they made for this purpose in a 01984 interview with Charles Stuckey:

We did an enormous poster for [Michael Heizer’s] Double Negative [01969]. I think it must be about 48 or 50 inches, which was in keeping with the mammoth endeavor of this work. It wasn’t just giganticism for its own sake; it really did relate to the work and get it across. So that communicated to people everywhere — collectors all over the country and in Europe were receiving this enormous poster. Primarily what we had were just photographs for the exhibition, but the intention was to communicate that the real exhibition was in Nevada. All right, it was under the auspices of the Dwan Gallery; Dwan Gallery’s main facility was in New York, but we also had this space out there which was a work of art, and if you really wanted to see the show, you should be out there. And that was revolutionary, to my knowledge. Virginia Dwan in Behind the Earth Movers (Boettger, 02004)

Indeed, in an almost-complete work of art called City, Heizer clearly considers size to be extremely important. “I think size is the most unused quotient in the sculptor’s repertoire because it requires lots of commitment and time,” he said. “To me it’s the best tool. With size you get space and atmosphere: atmosphere becomes volume. You stand in the shape, in the zone.’’

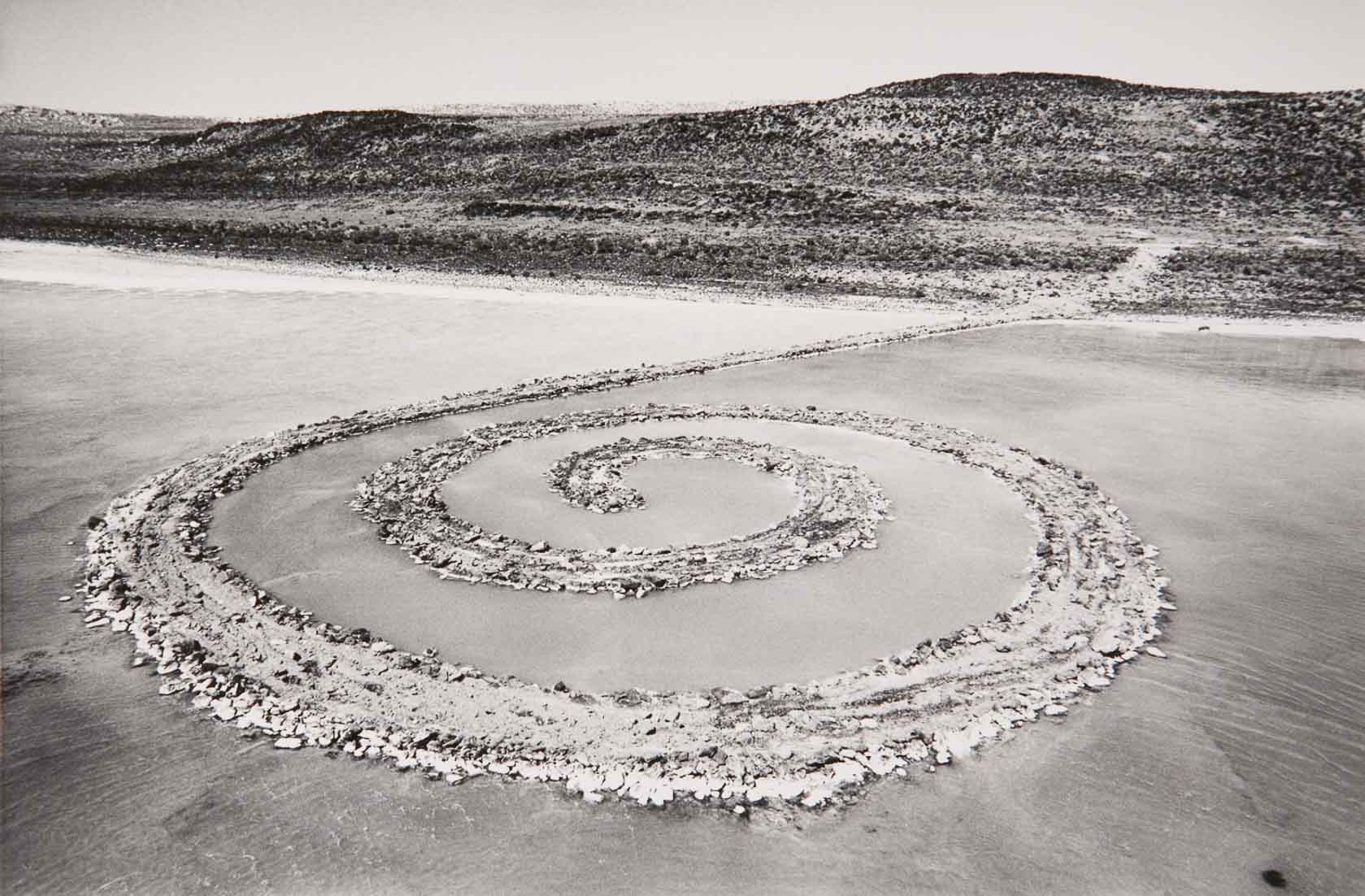

Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty is perhaps the most well-known and iconic of the early works of Land Art in the West. Smithson used trucks to dump black rock and dirt into the Great Salt Lake, forming a 1,500 foot long spiral that is revealed or concealed by the rising and falling of the reddish, salty lake water. He spoke of the work “as connecting distant futures and distant pasts.”

The relatively widespread familiarity with Spiral Jetty, however, is not necessarily due to people actually visiting the site. As with other Land Art projects, Smithson documented his work to be shown elsewhere, producing not just photographs but a half-hour film. Smithson wrote at length not only of the film, but of the process of creating it:

The movie began as a set of disconnections, a bramble of stabilized fragments taken from things obscure and fluid, ingredients trapped in a succession of frames, a stream of viscosities both still and moving. And the movie editor, bending over such a chaos of “takes” resembles a paleontologist sorting out glimpses of a world not yet together, a land that has yet to come to completion, a span of time unfinished, a spaceless limbo on some spiral reels. Film strips hung from the cutter’s rack, bits and pieces of Utah, out-takes overexposed and underexposed, masses of impenetrable material. The sun, the spiral, the salt buried in lengths of footage. Everything about movies and moviemaking is archaic and crude. One is transported by this Archeozoic medium into the earliest known geological eras. The movieola becomes a “time machine” that transforms trucks into dinosaurs. —Robert Smithson

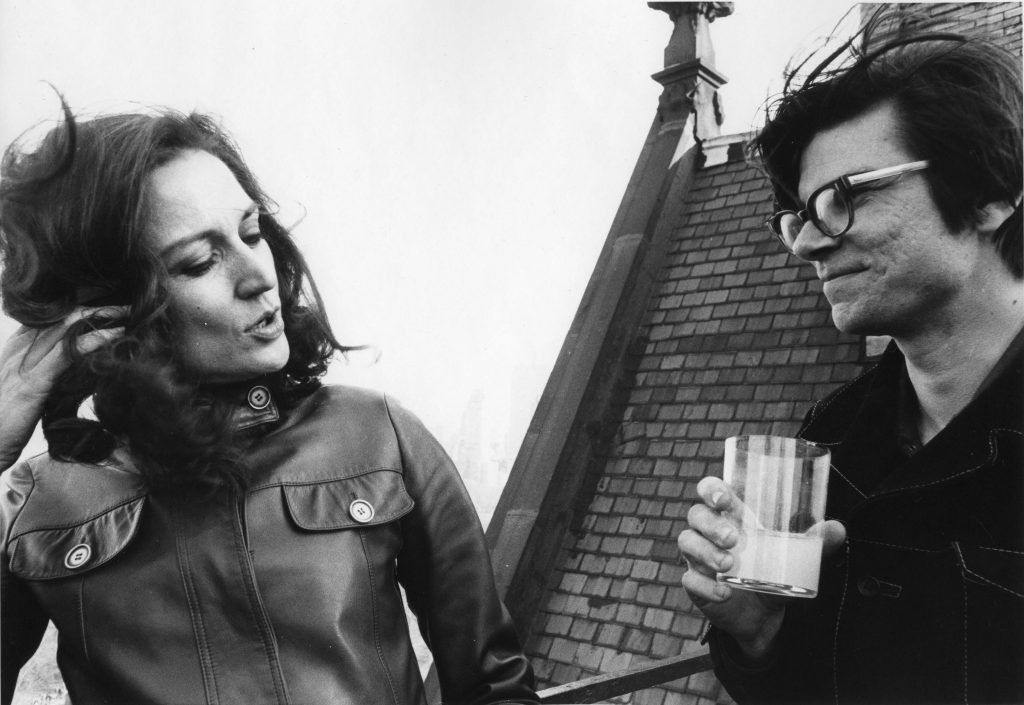

Nancy Holt, one of the original Land Artists, was married to Robert Smithson and involved in the earliest explorations of sites in the West. Sun Tunnels, one of her best known works, consists of four large concrete tunnels that are arranged so as to align with the sun in the middle of two of them on the solstices. Each one also has holes in the side that correspond to a celestial constellation.

Holt chose specifically to place the tunnels in the desert of Utah because, she writes, “the feeling of timelessness is overwhelming.” Like the other Land Artists, she addressed the site/non-site relationship by documenting her work extensively through still images and film; media she had studied while at Tufts University and which had a profound effect on her work.

Time is not just a mental concept or a mathematical abstraction in Utah’s Great Basin Desert. Time takes on a physical presence. The rocks in the distance are ageless; they have been deposited in layers over hundreds of thousands of years. Only ten miles south of the Sun Tunnels site are the Bonneville Salt Flats, one of the few areas in the world where you can actually see the curvature of the Earth. Being part of that kind of landscape and walking on earth that has never been walked on before evokes a sense of being on this planet, rotating in space, in universal time. —Nancy Holt, in Sculpting with the Environment: A Natural Dialogue (Oakes, 01995)

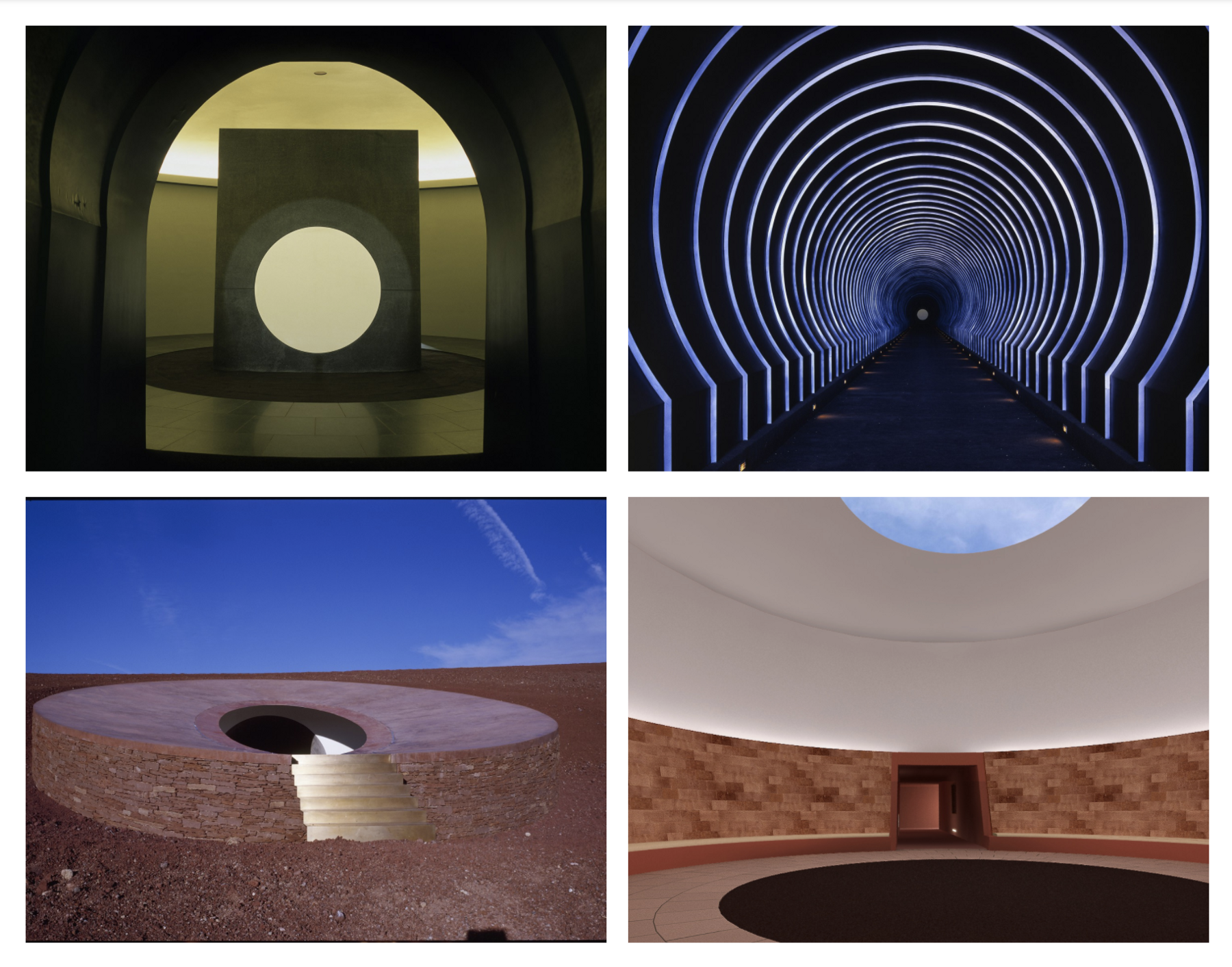

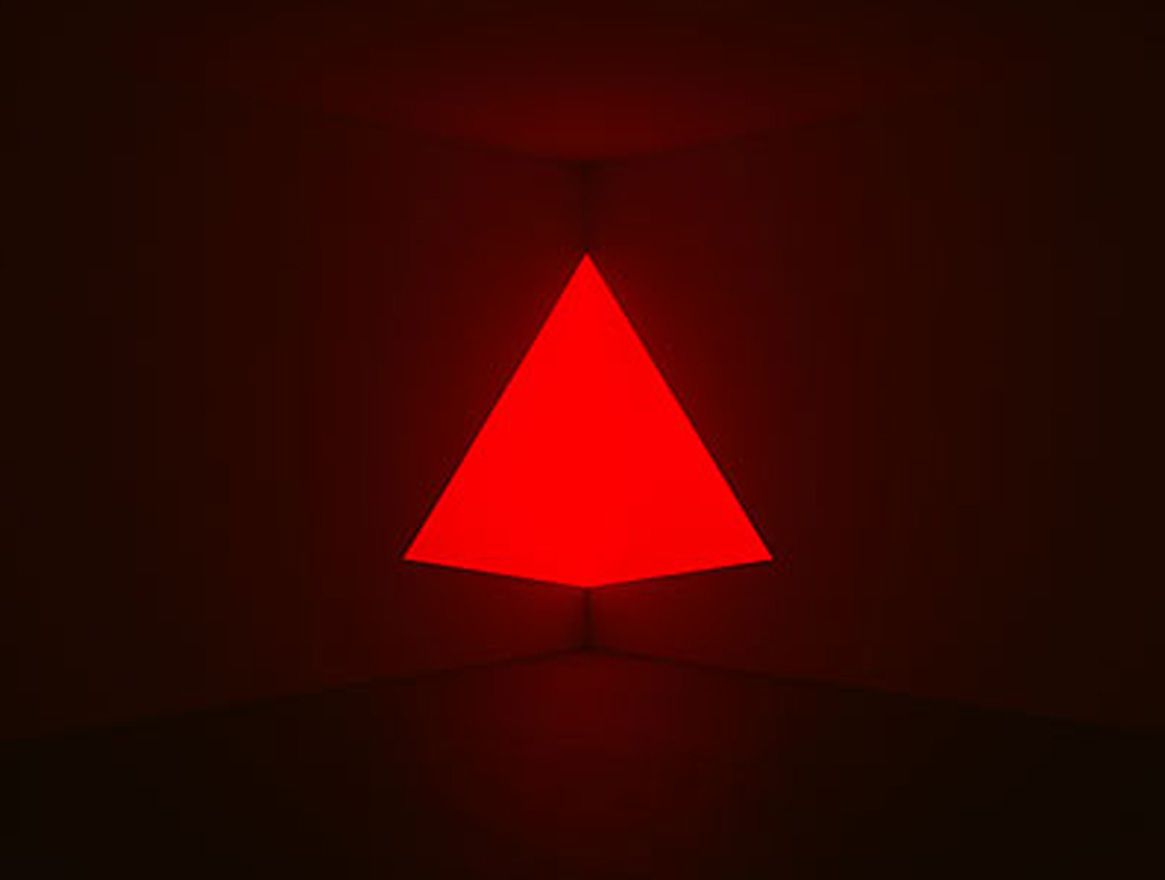

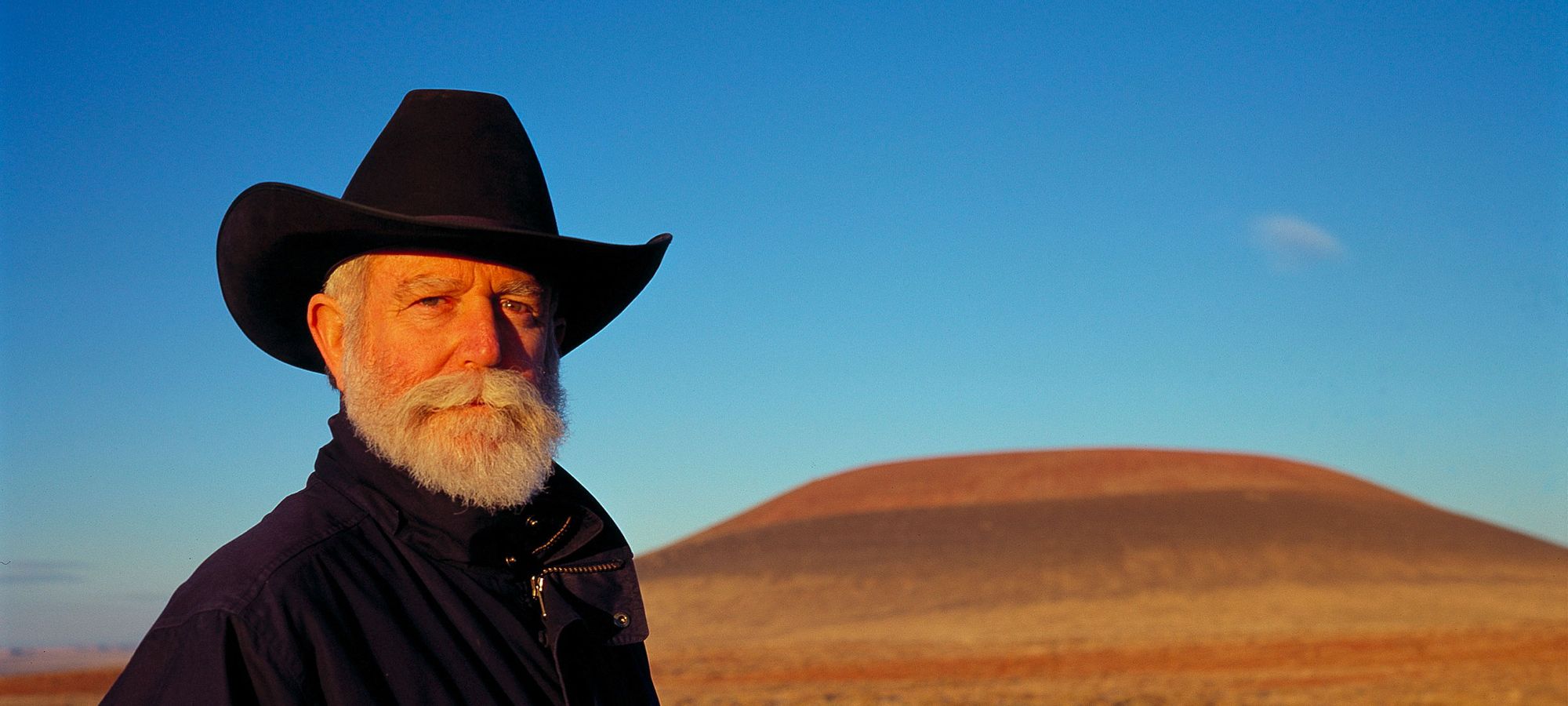

The Art of James Turrell

Amongst practitioners of Land Art, few can match the mythos surrounding James Turrell — owning a volcano will do that for you—but it would be hard to actually consider Turrell a card-carrying member of the movement even insofar as one existed in the first place. He wasn’t part of the Max’s Kansas City scene, he wasn’t part of the original “Earthworks” show at the Dwan Gallery and he’s continued to do gallery installations all over the world. Indeed, his work is probably better understood as installation art. Then again, there is that volcano he’s been molding, excavating and shaping for 30 years.

Turrell was born in 01943, grew up on the west coast, had a pilot’s license at 16 and studied perceptual psychology as an undergrad at Pomona College. His western roots, proficiency with planes and scientific curiosity, funneled through a Masters in Art at UC Irvine, would inform his work and eventually lead him to the Painted Desert and Roden Crater, a masterwork 39 years in the making he reportedly considers just 25 percent complete.

Despite the epic scale of most Land Art, Turrell’s path to it started with an interest in the minuscule. The infinitesimal particles and waves that make up light and the microscopic rods, cones and nerves we use to perceive them enchanted Turrell, leading him to reject the color wheel of art school in favor of the electromagnetic spectrum of perceptual psychology.

I look at the eye as the most exposed part of the brain, as something that is already forming perception.

– Turrell, from an interview with EGG

Color for Turrell is something that the viewer takes an active part in creating as a response to the cognitive input of various wavelengths of light. Instead of illuminating something with light, though, Turrell seeks to show his viewers the light itself, to manifest it in space as a perceivable object. His first experiments into projection began in Santa Monica in 01966 — right around the time Heizer and De Maria were making their first major marks in the ground — using an old hotel he converted into a studio. All sources of light but a select few were blocked, creating projections inside the space with light from the world outside.

I like to use light as a material. But my medium is really perception. I want you to sense yourself sensing. To see yourself seeing. To be aware of how you are forming the reality you see.

– Turrell, in an interview with Paul Trachtman

The eye, he explains, is most sensitive in low light — perhaps indicative of an evolutionary past spent hunting and hiding by moonlight — and so, by creating spaces that carefully control all light present, he can bring out our most discerning perceptive abilities and make visible phenomena we’d normally overlook.

His installations came to feature carefully lit voids that appear to the eye as glowing cubes, canvases or the sky itself brought within reach, that are revealed to be negative space only through attempts to touch them, or maybe a cloud drifting by. (He was famously sued by a woman who leaned against what she thought was a wall in one his installations.) In 01974, he began to imagine creating one of his sky space installations in a natural setting, which would bring him into the fold with Land Art, but it would be several years before he knew exactly where.

While he studied light and eyeballs and perception, Turrell was paying his way with a familial passion. His father had been an aeronautical engineer and passed on some of that expertise. Turrell maintained, restored and flew airplanes before his artistic pursuits paid for themselves. He became a licensed pilot at 16 and is rumored to have been flying Tibetan Monks over the Himalayas to escape the Chinese invasion not long after. Flight for Turrell isn’t divorced from his passion for perception, though — he often discusses illusions and visual phenomena experienced by pilots as an inspiration. His comfort and familiarity with planes and flying has informed his work and even made some of it possible — he flew over and around the West for months in search of the perfect site for his masterpiece:

I spent seven months flying the Western states, sleeping under the wing of the plane, and every third night staying in a Holiday Inn, to clean up.

– Turrell, interview in Art 21

The region north of Flagstaff, Arizona is a volcanic field littered with the pyramidal remains of a past geological epoch. Among them, Turrell happened upon the mile-wide, 700 foot-tall Roden Crater, uniquely isolated from other formations. Privately owned, it was bought in 01977 with funding from the Dia Arts Foundation, which eventually transferred ownership to Turrell’s own Skystone Foundation. Over the decades, Turrell has been planning, designing, fundraising and even ranching in the area of the crater. Construction is ongoing and may take many more years — Turrell has stopped offering even tentative projections for completion.

Once complete, Roden Crater will serve as an observatory unlike any other, with roots dating back far beyond the relatively nascent Land Art movement. Turrell aims to combine his years of experience manipulating and surprising the human eye with the awe and wonder people ascribed to the sky before artificial lights blocked it out. He hopes to bring people from the floor of the desert up into the sky, to inhabit it the way he feels one can while flying.

To that end, a series of 14 chambers below the Crater’s surface will amplify and accentuate the colors of the sky, the light of the stars and the glow of our galaxy. By isolating the emanations from beyond our galaxy from that of local stars, planets and our own sun and sky, Roden Crater allows visitors to take in different vintages of light ranging in age from just a few minutes to billions of years, to view subtle and rare phenomena amplified and projected, and to feel they’ve ascended beyond the surface of the earth.

As Land Art, it is easily the largest-scale, likely the most expensive, and possibly the most audacious piece to come out of the genre. Even still, a close look shows that its creator stands apart from many of the other Land Art practitioners in significant ways. No attempt at a non-site or off-site corollary seems to be in the works, perhaps because the installation so precisely manipulates the viewer’s sense of sight and so carefully reveals cosmological phenomena specific to a moment in time and a place in space. Additionally, the use of negative space and dirt has little to do with subverting commodification and elitism in the art world. The marks Turrell makes in the earth are a means — ideally invisible — to the end of shaping a direct experience with the cosmos that expands the viewer’s sense of self.

Whatever work it may take to get there doesn’t matter. I want you to see the swan as it glides across the lake, not the fact that underneath it’s paddling like hell.

– Turrell, in an interview with Paul Trachtman

Turrell may work with the earth, negative space, and celestial alignment like other practitioners of Land Art, but his thinking seems to operate on a wider range of scales. In the outward direction, he doesn’t stop at the earth, or the sky — with Roden Crater he is explicitly capturing and isolating light from beyond our galaxy. Inwardly, his work shrinks to the cellular and even the sub-atomic space of photons. These scales converge on the retinas of Turrell’s visitors to Roden Crater. There he’s worked with the earth, yes, but in the service of sharing with the viewer the power they themselves hold and the agency they exhibit in shaping and forming their perception of our universe.

Written by Austin Brown, Danielle Engelman, and Alex Mensing. Edited and updated by Ahmed Kabil.

Works Cited:

- Beardsley, John. Earthworks and Beyond: Contemporary Art in the Landscape. (1989)

- Boettger, Suzaan. Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties. (2004) & “Behind the Earth Movers,” Art in America. (April, 2004)

- Gilbert, Bill & Chris Taylor. Land Arts of the American West. (2003)

- Oakes, Baile. Sculpting with the Environment: A Natural Dialogue. (1995)