Scattered across Central and South America, small groups of birds have been dancing together for millions of years. Long before humans stood up and invented the kinds of things we’re proud of — like the iPhone, or the hyperlink, or the wedge — these birds were dancing. As our trends rose and fell in a relative blink of an eye they kept dancing. These birds have achieved something we have not: doing something lovely, dancing, without pause or self-catastrophe, for so long. How is it possible?

These birds are manakins, nearly 60 species that compose the scientific family Pipridae. Like their more famous counterparts in southeast Asia, the birds-of-paradise, manakins are known for their sex lives. In most manakin species, males spend their lives competing for the attention of females, hoping to woo a mate and, well, copulate. But where birds-of-paradise grew dedicated to fancy plumages — different species with their shock-blue skin, abyss-black cowls, or lifting, filigree plumes — manakins grew invested in dancing.

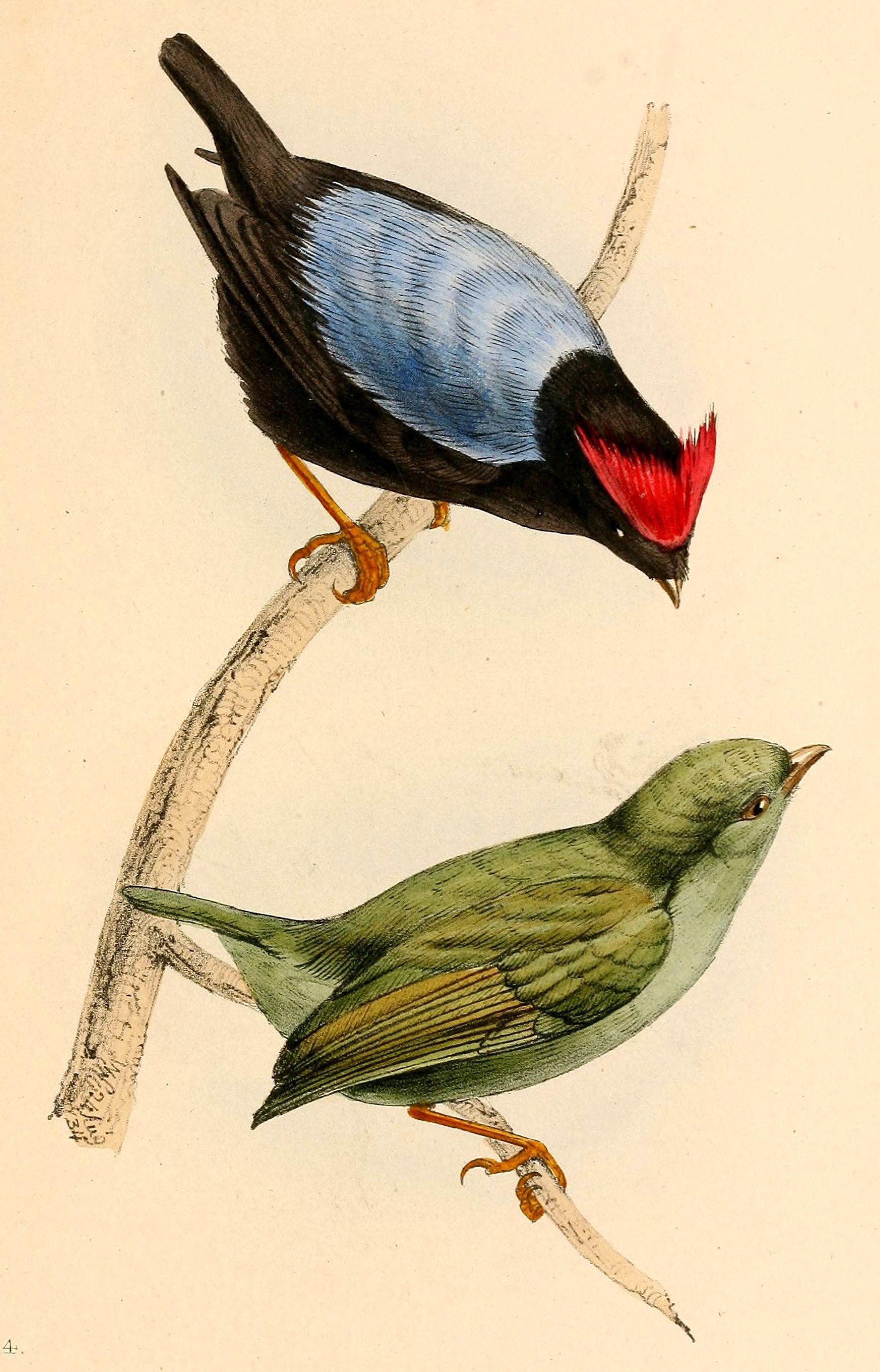

Don’t get me wrong, these birds look beautiful. As a young ornithologist, eager to do fieldwork, I had the good luck of joining Dr. David McDonald and Nicholas Oakley in their fieldwork on manakins in the cloud forests of Ecuador. I remember holding our prized study species, the Golden-winged Manakin (Masius chrysopterus). They are as big as apricots and as light as kumquats. Females and young males wear a soft green with yellow highlights. The older males grow into a coal black body, a poofy yellow forehead, and a lizard-like run of scaly feathers down the back of their necks.

Yet striking as they are, I didn’t understand the birds until I saw them move. It usually went like this: a log rests at a slight angle on a muddy hillside, a soft spotlight of sunshine center stage. If you sit quietly you’ll hear a descending whistle, like the classic foley of a dropping bomb. Then a male Golden-winged Manakin will splash down on the log, impact feet first, rebound, and with a pop land just a few inches further up the log.

It’s hard to tell what’s happening in those brief, hectic moments. McDonald, Oakley, and I hauled a high speed camera down the trails of an Ecuadorian cloud-forest to see more. The footage is striking. A female lands on the middle of the log, tilting her head to observe the canopy. When seen in slow motion, the male blasts into the corner of the screen, careening towards the log. He flashes open his wings and tail to reveal bright, hidden patches of gold. He lands a few steps in front of the female, then twisting his entire body, arcs over her head. She pivots to watch. He sticks the landing.

In watching this bird watch this bird, we get our first clue about how — and why — manakins have danced together for so long. As Dr. Richard Prum explains in his book The Evolution of Beauty, a male manakin has no chance to reproduce except through the consent of a female. No matter how strong or weak, smart or dumb, sick or healthy, a male Golden-winged Manakin has to impress a female if he wants to sire young. We know precious little about what, exactly, impresses a female manakin. What is clear is that individuals in most species only choose mates who dance. So, manakins dance.

Females will only mate with males who do the right dance. But males are not being coerced into dancing. These birds are free to do what they might with their birdy lives. If I were a young male manakin, I think I could make a perfect life of eating fruit in the cool fog of the high Andean morning. It is just that most manakins are not so content. They prefer to impress females, who prefer vaults around mossy logs.

A lesson from birds, then: there exist reasons to dance for one another that are neither obligations nor inevitabilities. There are ties that are not bindings.

Intergenerational Chains

Some species of manakins have gotten even more tangled up with one another. At one mossy log, I remember watching three male Golden-winged Manakins dance in sequence. One would dive, then flip, then flutter off as another came diving. In this species, multiple males seem to dance together only for occasional practice, though never in front of a female audience.

In other species, multi-male dances have become a more fundamental part of social and sexual life. Long-tailed Manakins are one extreme case. Female Long-tailed Manakins only choose mates who perform a cooperative display involving two dance partners. Males will sit together on a small display branch and twitter a small song, an announcement. If a female arrives, they will begin to cartwheel over one another, lifting their small bodies — deep black with twin delicate tail streamers, a sky blue mantle, and the flat punctuation of a red cap — over their dance partner, hovering a few inches backwards in the air, and dropping down to queue again behind their partner. If the female favors the dance, she will choose to copulate with the lead dancer of the pair.

Long-tailed Manakins dances are organized at multiple social levels. A male displays with another male as part of a dance team. These dance teams perform for females. Yet these dance teams are merely the top players in a hierarchical queue of up to 15 males: an entire dance troupe, waiting in the wings. Research by McDonald suggests Long-tailed Manakin females care about — and remember — the behavior of the entire dance troupe, rather than specific dance teams or individual dancers. Females visit troupes that performed impressive dances in the past, even when the dancing males have changed. For Long-tailed Manakins, a dance troupe is thus a kind of institution. It links dancers with one another, and with audiences, beyond the life, death, or behavior of any individual bird.

Birds die, and dance troupes fall apart. The oldest known Long-tailed Manakin was 18 years old. No small feat for a bird weighing in at four US nickels. But any finite lifespan can make manakin dances look transient. An evolutionary view looks different. The closest relatives of Long-tailed Manakins, the other species in the scientific genus Chiroxiphia, also perform cooperative displays, with dance teams and troupes. As Richard Prum reasoned in his 01994 research on manakins, these shared qualities imply cooperative displays evolved in the common ancestor of Chiroxiphia lineage. In 02020, new genetic evidence determined that this ancestral lineage is at least 2 million years old. Out there in the forest, an intergenerational chain of Chiroxiphia dance troupes has been performing all this time. This society is orders of magnitude older than even the most ancient of human institutions. Indeed, the chain of dance troupes predates Homo sapiens itself.

Slow Changes, Deep Invention

One difference between manakin institutions and human institutions may be key to their longevity: manakin institutions are deeply social, but they are not, so to speak, cultural. When we think of human institutions, we often think of the ways in which humans learn directly from one another. For example, an artist might see a beautiful painting and copy one of its techniques. Or one engineer might teach another how to build a new tool. Biologists have long studied culture in non-human animals, too. Many famous examples involve singing. Whales learn the songs of families, and many birds learn the songs of their neighbors.

Manakins do not participate in these kinds of cultural learning. As far as we know, the songs and dances in these species emerge from their bodies rather than being learned from others. Unlike a sparrow or robin, a Long-tailed Manakin will never altogether learn how to sing a song directly from another male.

The absence of cultural learning could play a key role in the longevity of manakin dances. For all the unconstrained innovations of culture — the new art, the new tools — the same innovation can erase the past. I am writing this with wireless headphones (right now, they are delivering “For the Snakes” by The Mountain Goats at a pretty severe volume). Last year, my earbuds had wires. I am just old enough to remember the thin foam of my Walkman’s headphones and the click of its CD closure. These inventions built on one another, and solved problems. But there are things I do not remember: the tape deck, the radio broadcast, the turntable, the phonograph, the church chorus, the firepit song. The rapid, complete innovation of human culture can be the very thing that leads us to replace, and ultimately forget, what came before.

Manakins invent at a slower pace. Another of Prum’s research publications found that snippets of manakin dance moves have been preserved over vast, evolutionary time. For example, the dive-and-rebound dance move of the Golden-winged Manakin closely resembles a similar routine in the White-throated Manakin. The last time these two species shared a common ancestor was at least 4 million years ago.

Rather than teaching one another new dances within each generation, manakins invent their dances at a slower pace, across generations. Although the dances of Golden-winged and White-throated manakins betray an ancient resemblance, these species have also evolved key differences in their routines. For example, Golden-winged Manakins end their dives in a chin-down pose, showing off the scaly feathers on the back of their neck. Meanwhile, White-throated Manakins hold a chin-up pose, showing off their eponymous white necks.

A similar pattern holds across the entire manakin tree of life. Closely-related species share core elements of their dances, though most show small alterations that match their unique bodies, plumage, or display sites. Over longer timescales, these small inventions have added up to entirely new forms of dancing. Some manakins shiver their wings to produce a high, cricket-like song, others moonwalk across branches, and still others snap back and forth between upright sticks on an open dance floor.

In each case, unique dances appear to impress the females of a given species. Female preference thus plays a twin role in the longevity of the manakin’s forever-dancing. On the one hand, female preference is the very reason that manakins keep dancing after all these years. The reproductive need to display for females is a kind of preserving force, which keeps manakins dancing over long periods of time. On the other hand, female preference is also a creative force. Whenever female preference evolves across species, male dances evolve with it. As Prum writes in The Evolution of Beauty, manakin dance sites are thus “among nature’s most creative and extreme laboratories of aesthetic evolution.” Manakin society is creative precisely because the birds are preserving something: coming together, being caught up with one another, over and over, in dancing.

Social invention goes beyond dances themselves, to restructure the entire lives of manakins. Some of my own research focuses on young male manakins, some of whom spend years in a drab, green plumage before they dress up in the brighter feathers of older male dancers. As Laura Schaedler, myself, and colleagues reviewed in 02021, these plumages have likely evolved as social signals that help young males avoid aggression from older birds. Every generation, young males enter into manakin society afresh. If they want to reproduce, they must find a display site and practice their displays. In cooperative species such as the Long-tailed Manakin, males must also join a dance troupe and build relationships with future dance partners. By being green, rather than bright and bold, young birds may signal that they are here to develop their skills, not to compete — for the time being, that is. The evolution of these green plumages again reveals the tension sustaining manakin society. Young males stay in close quarters with one another — a preserving process, which re-establishes social relationships generation after generation. To do so, they have evolved plumages that allow for new, less-hostile kinds of relationships — a creative process, which slowly choreographs social relationships.

Small, colorful, gymnastic birds have in this way spent millions of years reinventing with one another, seducing and assessing, dancing and watching dances. They have found reasons to dance, have built institutions around them, and within the rules of those institutions carved ample room to elaborate.

There is only one clear threat to the manakin’s dance: us. Not everyone — not “humans” — but those of us organizing the global economy that wreaks enormous damage on manakins and their forests. Despite political promises, tropical forests are continuing to disappear. Burned to host cattle for what, for cheap steak and the thrill of venturing capital for cheaper steak. One beautiful species, the Araripe Manakin, survives in just 30 miles of Brazilian forest. Male Araripe Manakins are blazing white, with black wings, a black tail, and a thunderous red crown running from forehead to mantle. Critically endangered and described to science less than 30 years ago, the birds have a strange mating system with no dance displays. One possibility is this species represents a unique evolutionary twist on manakin society, involving male competition rather than male cooperation and dancing. Another possibility is we killed enough birds to destroy a society. It is too late to know.

Manakins owe us nothing. Nor do these birds exist as a lesson. Indeed, we can never look to nature for moral instructions. Despite all this, manakins are offering us an example. They show us a way of not only persisting, but also inventing, for millions of years. Manakins show us something is possible. It takes preservation, creativity, and a place to live.