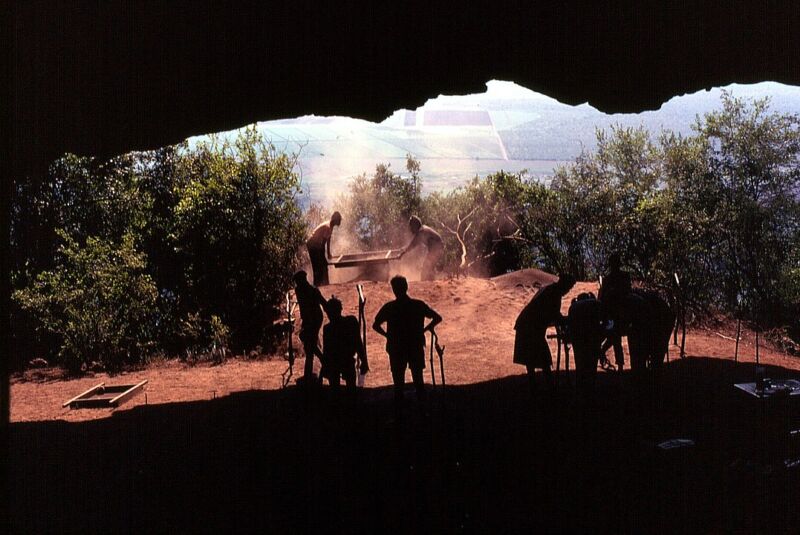

The oldest beds known to science now date back nearly a quarter of a million years: traces of silicate from woven grasses found in the back of Border Cave (in South Africa, which has a nearly continuous record of occupation dating back to 200,000 BCE).

Ars Technica reports:

Most of the artifacts that survive from more than a few thousand years ago are made of stone and bone; even wooden tools are rare. That means we tend to think of the Paleolithic in terms of hard, sharp stone tools and the bones of butchered animals. Through that lens, life looks very harsh—perhaps even harsher than it really was. Most of the human experience is missing from the archaeological record, including creature comforts like soft, clean beds.

Given recent work on the epidemic of modern orthodontic issues caused in part by sleeping with “bad oral posture” due to too-soft bedding, it seems like the bed may be another frontier for paleo re-thinking of high-tech life. (See also the controversies over barefoot running, prehistoric diets, and countless other forms of atavism emerging from our future-shocked society.) When technological innovation shuffles the “pace layers” of human existence, changing the built environment faster than bodies can adapt, sometimes comfort’s micro-scale horizon undermines the longer, slower beat of health.

Another plus to making beds of grass is their disposability and integration with the rest of ancient life:

Besides being much softer than the cave floor, these ancient beds were probably surprisingly clean. Burning dirty bedding would have helped cut down on problems with bedbugs, lice, and fleas, not to mention unpleasant smells. [Paleoanthropologist Lyn] Wadley and her colleagues suggest that people at Border Cave may even have raked some extra ashes in from nearby hearths ‘to create a clean, odor-controlled base for bedding.’

And charcoal found in the bedding layers includes bits of an aromatic camphor bush; some modern African cultures use another closely related camphor bush in their plant bedding as an insect repellent. The ash may have helped, too; Wadley and her colleagues note that ‘several ethnographies report that ash repels crawling insects, which cannot easily move through the fine powder because it blocks their breathing and biting apparatus and eventually leaves them dehydrated.’

Finding beds as old as Homo sapiens itself revives the (not quite as old) debate about what makes us human. Defining our humanity as “artists” or “ritualists” seems to weave together modern definitions of technology and craft, ceremony and expression, just as early people wove together sedges for a place to sleep. At least, they are the evidence of a much more holistic, integrated way of life — one that found every possible synergy between day and night, cooking and sleeping:

Imagine that you’ve just burned your old, stale bedding and laid down a fresh layer of grass sheaves. They’re still springy and soft, and the ash beneath is still warm. You curl up and breathe in the tingly scent of camphor, reassured that the mosquitoes will let you sleep in peace. Nearby, a hearth fire crackles and pops, and you stretch your feet toward it to warm your toes. You nudge aside a sharp flake of flint from the blade you were making earlier in the day, then drift off to sleep.