LEARN MORE

The first time I saw speculative futures used to shape cities, I was standing on the work. It was an April evening years ago, and I was headed to a client meeting. I hustled from my car toward the building in question, my arms full of rolled paper, when I noticed a series of questions chalked in block letters on the sidewalk below my feet.

I wish this was _________ the words called out. A statement followed by an empty line, stretching out like an invitation.

The sidewalk fronted an empty lot, surrounded by a chain link fence. Save for a few clumps of grass and plastic bags, the lot was empty. The sidewalk in front of it, however, was full. Chalked statements spread across the cracked pavement, each starting with the same phrase: I wish this was _________. Pieces of chalk lay scattered along the sidewalk’s edge, which previous passersby had used to fill in the blanks. I wish this was A PARK. I wish this was A GARDEN. I wish this was A GLOW IN THE DARK DANCE FLOOR.

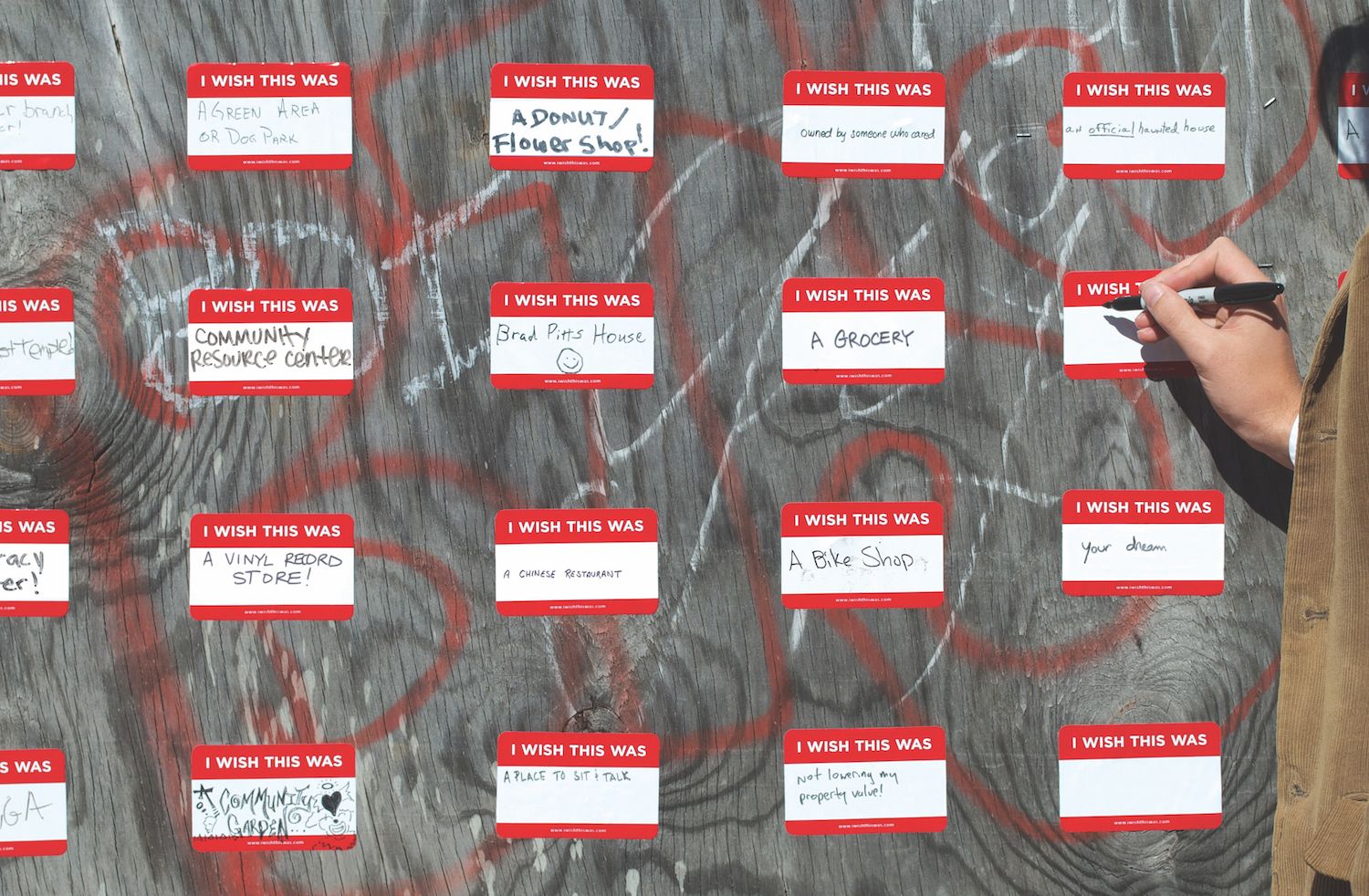

I later learned that the effort was a replica of work by the artist Candy Chang. She had done a series of public installations in the mid-02000s, pasting stickers on vacant city buildings in New Orleans.1 Each was printed with the words I wish this was _________. Her stickers were a question and statement both, transforming boarded-up windows and weathered siding into spaces where people shared their dreams about what could be. It was a simple kind of speculative futures approach, an invitation to ask “what if?” and “why not?”

Standing on the sidewalk that April evening, staring at the words chalked on the ground, I didn’t understand that bigger context. I didn’t know Chang existed. I didn’t know that “what if?” questions were fundamental to the speculative futures field. I didn’t know what speculative futures was. I just thought the phrases were a playful way to spark public conversation about the vacant lot’s future. People were voluntarily—happily, it seemed—brainstorming what the site could be.

I wanted to join, to skip the scheduled client meeting and add my ideas to the growing list. But since I also didn’t want to lose my job, I hurried toward the building.

Asking what people want vacant lots to become is one of many reasons to use speculative futures. Silicon Valley companies apply the tools to prototype new technologies. International governments harness them to shape long-term development strategies. Hollywood studios ensure the success of franchises like Star Wars and the Marvel Cinematic Universe by building on their principles.

The various approaches form an amorphous field, with little agreement on definitions or applications. To steal the words of researchers Shelley Streeby, Nalo Hopkinson, and Christopher Fan, I’ve come to understand speculative futures as “an umbrella … under which a wide range of strategies for world-making and imagining the future … are situated.”2 Although the tactics under the umbrella are distinct, they all use story-based speculation to explore alternative worlds. Peering into the future is what helps us reflect on current conditions and the long-term ramifications of choice.

It’s this gap between fantasy and reality that’s both where imagination lives and where real change can occur.3 Imagination massages the space between what could be and what is, transforming future uncertainties and hopes into present-day decisions. Speculative futures harnesses imagination to translate fantasy into reality.

For people involved in the work of building cities, that gap is familiar. Urban planning is a speculative storytelling exercise, one where alternative versions of city space are explored, evaluated, and enacted over time. Designers and architects envision new possibilities for districts, transit systems, and plazas, then work to build them in physical form.

Historically, the space between fantasy and reality has been key to promoting idealized visions of city life. Ebenezer Howard’s nineteenth-century plan of the “Garden City” was a speculative vision of what he saw as necessary change. This was 01898, at the tail end of the first wave of the Industrial Revolution, when urban centers were plagued by overcrowding, pollution, and disease. Howard proposed a radical alternative—move people out to the country and have them commute to work by railroad, trams, and (eventually) cars. His Garden City started off as an imaginary suburban ideal, but it was such a convincing solution that it dominated city making throughout the twentieth century.

Speculating about the future to predict and persuade is still a dominant part of how cities are made today. In 02020, the Danish architect Bjarke Ingels released a plan for the entire Earth. Titled Masterplanet, the project attempts to show that humanity can use already-existing technologies to have both a sustainable footprint on the planet and a high quality of life.4 While this kind of visionary thinking is inspiring, it promotes the belief that the right blend of technological tools, spatial strategies, and expertise inevitably leads to good solutions. A review of the project in Time magazine pointed out that “even in a world where the COVID-19 pandemic has transformed our understanding of what is possible in terms of collective responses to a global challenge, it’s all but impossible to imagine any single climate plan achieving meaningful uptake from industries, governments and communities around the world.”5 Like Howard over a century ago, Ingels focuses on the power of technological tactics and land-use strategies to predict a potential future and persuade others to agree.

Architects and developers have reason to present their ideas as predictions. Cultivating a compelling vision of what doesn’t exist requires more than imagination. It demands funding and support. An idea without the backing to bring it to life is just another idea. And backing is easiest to secure when the proposal at hand doesn’t offer a mere possibility of success, but a guarantee. Presenting a project as a certainty is a safer bet.

Yet certainty isn’t safe. Projects billed as solid regularly fall short of their original promises. Schemes that initially appear sure-fire can’t always adapt to climatic changes, demographic shifts, or funding gaps. Approaching city making as a process with guaranteed results perpetuates the idea that the future can be forecasted and controlled. That kind of thinking is dangerous. Summer temperatures will continue to spike higher than existing cooling systems have been designed to handle. Internet access and storage demands are already outpacing available tools. Even with the best research and foresight, urban life will continue to morph in ways beyond prediction. The past is not a sufficient template for what lies ahead.

Aiming for prediction also extends urban development’s long legacies of exclusion. For generations, the work of city making has limited public participation to minimize opposition and accelerate built work.6 Many communities have been dismissed, disenfranchised, and displaced as a result, setting the stage for many of the social and economic inequalities plaguing cities today. Prioritizing approval over collaboration reinforces those exclusive patterns, prolonging the narrative that cities are spaces for experts to shape. When imagination is a means for persuasion in development, the benefits of a particular design are rarely evenly distributed.7

Clinging to threads of certainty ultimately limits our imagination about what cities can become. Presenting futures as predictable requires grounding them in today’s logic. Yet the confines of conventional wisdom often turn envisioning alternative trajectories into impossible tasks. Because environmental degradation is progressing at increasingly rapid rates, it’s easy to assume total devastation is inevitable. Because exclusive planning is still the widespread norm, pushing for collaboration can feel impossible. Because privatization and deregulation have dominated Western societies for decades, many of us can’t picture a future without them. Placing boundaries around collective imagination makes long-standing issues appear increasingly intractable and dystopian futures more inevitable by the day.

By exploring what’s possible, speculative futures cultivates critical thinking about the present and imagination of what lies ahead. The field embraces the fact that what we call “the future” is a construct, an amalgamation of assumptions, interpretations, and inferences based on experience, research, and hope. Rather than presenting ideas of where the future can go as certainties, speculative futures works with those constructs, employing dynamic tools for prototyping, testing, and evaluating the ramifications of where our imaginations can lead.

Celebrating the space between fantasy and reality builds the resilience this century requires. Studies show that actively imagining the future cultivates psychological strength, helping individuals feel more prepared and resourceful during times of drastic change.8 Skill in envisioning potential futures increases our understanding that present-day choices affect how the future unfolds. Instead of craving extensions of the familiar, we can learn to find power in crafting proactive decisions. Doing so augments our personal agency, well-being, and resilience.

When practiced across communities, imaginatively working with the future builds what researchers call social resilience. Increasingly recognized as critical to navigating intense and unpredictable change, social resilience is a group’s ability to cope with adversity, adapt to challenges, and build shared prosperity over time.9 When imagining different futures becomes a collaborative process, the results augment our adaptive capacities.10 Developing shared visions requires and builds trust, cultivating the kinds of connections that help societies weather the unpredictable.11

Negotiating modern change demands the personal and social resilience imagination fosters. Technological, political, and climatic disruption will only accelerate in coming years. How these changes will play out over time defies prediction—there are too many inputs out of our control.

If we want to aim toward less-dystopian destinations, we have to get creative. Our survival on this planet depends on creating nimble responses to accelerating scales, scopes, and speeds of change. By creating containers for collective imagination of what the future can bring, speculative futures helps us create those responses together.

They do so in part by translating uncertainty into hope. As writer Helen Macdonald declared in the New York Times, “To keep hope for the future alive we have to consider it as still uncertain, have to believe that concerted, collective human action might yet avert disaster.”12 Speculative futures cultivates that hope by expanding how we articulate what the future can become.

Assuming that devastation is the entirety of what’s ahead is limited thinking. What if the best times are still to come? We owe it to ourselves to ask. Speculative futures are tools to help us in the asking and co-create the answers we find.

—

Adapted from Speculative Futures by Johanna Hoffman, published on October 4, 02022 by North Atlantic Books. Hoffman will be speaking at Long Now on October 12, 02022.

Notes

1. Chang’s work was a response in part to vacancies caused in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. A resident of the city, she wanted to start a community dialogue about what the many vacant buildings in her area could become. When she found local planning meetings to be overly prescriptive, slow, and low on imagination, she took matters into her own hands and printed the stickers (Chang 02020).

2. Streeby, Hopkinson, and Fan 02019.

3. Paul Dobraszczyk describes the dynamic in Future Cities: Architecture and the Imagination, writing that “(t)he imagination is both an active agent—a way of constituting something—and also a transformative faculty.”

4. Block 02020.

5. Nugent 02020.

6. Smith 01973.

7. Yazar et al. 02020.

8. Sools and Mooren 02012.

9. Keck and Sakdapolrak 02013.

10. Fuchs and Thaler 02018.

11. Goldstein 02018; Adger 02006; Milman and Short 02008; Wamsler 02013.

12. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/13/magazine/dune-denis-villeneuve.html