Imminent climate catastrophe. An unending pandemic. Rampant authoritarianism. Unceasing incarceration in the United States. Half of the United States unable to afford one $400 emergency. Grossly concentrated global wealth and 1.7 billion workers in the world residing in countries where inflation outpaces wages. A significant increase in the number of people going hungry across the globe. Some 574 million people worldwide expected to endure extreme poverty by 02030 if trends continue.

Interrelated crises abound, and the effects are felt not just in one country or a couple of countries, but across the planet. To address the crises, then, we probably ought not to take an individual nation-state as the primary unit of analysis or as the key site for transformative action.

If we operate under the ostensibly reasonable assumption that existing crises reflect sometimes difficult-to-detect historical developments, then we also ought to concern ourselves with the longue durée. The French historian Fernand Braudel and the Annales School, a tradition rooted in the study of long duration social history, popularized the concept.

“My understanding of the longue durée is that it's something that takes place over many, many centuries, if not millennia,” Omer Awass, an associate professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies at American Islamic College.

Awass is what you might call a world-systems theorist.

At the core of world-systems thinking is the need to pay attention to and glean insights from the slow-moving historical changes that occur over the long-term, over what world-systems scholars refer to and study as the longue durée, so as to throw light on the chaotic, rapidly changing reality we live in now.

Looking at the longue durée with a world-systems lens reveals the flawed contours of our social order, like the economic imperative to subordinate the concerns of most human beings to institutionalized pressures to commodify, grow, maximize profit and accumulate capital while concentrating influence and decision-making power.

Taking the world-system, rather than a nation-state or conventional geopolitics, as the primary unit of analysis clarifies why previous attempts to realize lasting, uplifting transformative change have too often proven largely if not wholly ineffective — and in some instances disastrous. The aims of national liberation struggles and revolutionary efforts to attain and exercise state power to drastically improve people’s lives never fully materialized or endured, world-systems analysis informs us, because of the larger systemic forces at work.

Immanuel Wallerstein, perhaps the most prominent and prolific proponent of world-systems analysis, suggested that those systemic forces include the imperative to accumulate capital. They include the disparate power relations between nation-states that have expanded capital accumulation. Those features of the system prioritize constant production of surplus at the expense of people disadvantaged by existing arrangements and at the increased risk of exacerbating existential crises, ecological and otherwise.

Recalibrating our focus to the structures extending beyond and influencing international as well as intra-national relations helps us grasp why interventions at national scales likely won’t do more than provide partial palliatives for the deeper ills of the world, sans fundamental shifts in how we organize and maintain our interconnected lives.

The End of the World-System as We Know It

When it comes to understanding the crises as well as the opportunities we face today, Wallerstein’s analysis also offers an apropos insight, or a prophetic prognostication, if we wish to entertain his theory with greater skepticism. Prior to his death in 02019, Wallerstein claimed that, since at least the 01970s, our modern world-system has been in a period of structural crisis. For him and for many world-systems scholars, the upturns and downturns of the capitalist world-economy that the system has cycled through for centuries, perhaps longer, have pushed it further and further away from equilibrium, to a point of no return.

“The primary characteristic of a structural crisis is chaos,” Wallerstein wrote in an essay from 02011. “Chaos is not a situation of totally random happenings. It is a situation of rapid and constant fluctuations in all the parameters of the historical system. This includes not only the world-economy, the inter-state system, and cultural-ideological currents, but also the availability of life resources, climatic conditions, and pandemics.”

Those wild fluctuations emerge from and compound the crises that surround us.

“Because the fluctuations are so wild, there is little pressure to return to equilibrium,” Wallerstein argued in a 02010 essay, explaining our predicament. “During the long, ‘normal’ lifetime of the system, such pressure was the reason why extensive social mobilizations — so-called ‘revolutions’ — had always been limited in their effects. But when the system is far from equilibrium, the opposite can happen—small social mobilizations can have very great repercussions, what complexity science refers to as the ‘butterfly effect’. We might also call it the moment when political agency prevails over structural determinism.”

A world-systems perspective on the formation and long-term transformation of enduring social arrangements can help us understand how social movements and perhaps our own personal actions and interactions might tilt the balance to bring about a better successor system, or at least give us a greater understanding of what it would take to improve human lives during these tumultuous times.

If capitalism and the somewhat synonymous modern world-system that has sustained it are ending sooner rather than later, per Wallerstein’s view, or even if we just wish to address the underlying sources of our interrelated problems, world-systems analysis offers unique insight into what not to keep doing. It helps identify the repeated large-scale patterns that must be discontinued and displaced to build a better world.

A brief genealogy of system history informed by the thoughts of those using world-systems theory should help hone that perspective.

500 Years or 5,000?

Not all world-systems thinkers have understood the longue durée of the existing system in the same way. While Wallerstein believed it’s a 500-year-old system that’s coming to an end, what if the system dates back much farther — say, 5,000 years? A different perspective on its origins can alter our understanding of how it may end or what successor system(s) arise in its wake. At the same time, extending the longue durée view of the system could affect our grasp of its fundamental qualities, what must be transformed within it, and what social arrangements are possible beyond it.

Andre Gunder Frank, one of Wallerstein’s friends and contemporaries, took a more continuationist view of system history. Frank, along with Barry Gills, claimed enduring features of the system, like constant capital accumulation, date back several millennia and occurred throughout the world system via investment in agriculture, livestock, industry, transport, commerce, militaries and other means. In “The World System: 500 Years or 5,000?,” Frank and Gills suggested the motor force of capital accumulation and a shifting hierarchy of center-periphery complexes dates back more than just a few centuries. Wallerstein and another first generation world-systems scholar, Samir Amin, undervalued the significance of trade and market activity in the ancient world, causing them to overlook the role certain people or areas played in the development of the “world political-economic system” that’s displayed the same “structural patterns and processes for at least 5,000 years,” Frank and Gills explained.

They saw capital being accumulated, surplus being generated, and different regions benefiting disproportionately from the transfer of that surplus way before the 16th century European point that many sources, including Wallerstein, place it at. Both perspectives theorize a capitalist system that predates the industrial capitalism that Karl Marx critiqued in the nineteenth century when he analyzed the production of capital that occurred under harsh conditions in England’s factories.

If Wallerstein, Marx, and others identified qualitative shifts in social relations that became significant more recently than 5,000 years ago, adopting a continuationist view of history with an insistence on seeing enduring features of the system as several-millennia-old could make it difficult for people to imagine other possible arrangements. The late David Graeber, an anthropologist and one of the organizers of the initial Occupy Wall Street encampment in New York City circa 02011, suggested as much in a journal article which called into question the tendency to see shades of capitalism everywhere.

Graeber might have been right about the challenges associated with imagining and realizing better worlds when we privilege the longue durée over interest in the experience of social relations, focusing on the cumulative production of surplus and capital over the production of people. Yet Frank and Gills’ millennia-encompassing view of developing systemic interactions also alerts us to overlooked processes operating on grander timescales. That view brings into focus enduring arrangements responsible for disparities and sociological phenomena that we would be foolish to tie solely to post-01800 institutions.

Moreover, dating the origins of the system back several millennia might ironically even help us imagine how socioeconomic relations might be otherwise, à la Graeber.

A closer look at the work of David Wilkinson, a professor of political science at UCLA who contributed a chapter — “Civilizations, Cores, World Economies, And Oikumenes” — to the aforementioned Frank and Gills text reveals some of those imaginaries. Wilkinson opted for the framework of civilizations, which he referred to as vast social entities that “transcend the geographical boundaries of national, state, economic, linguistic, cultural, or religious groups.”

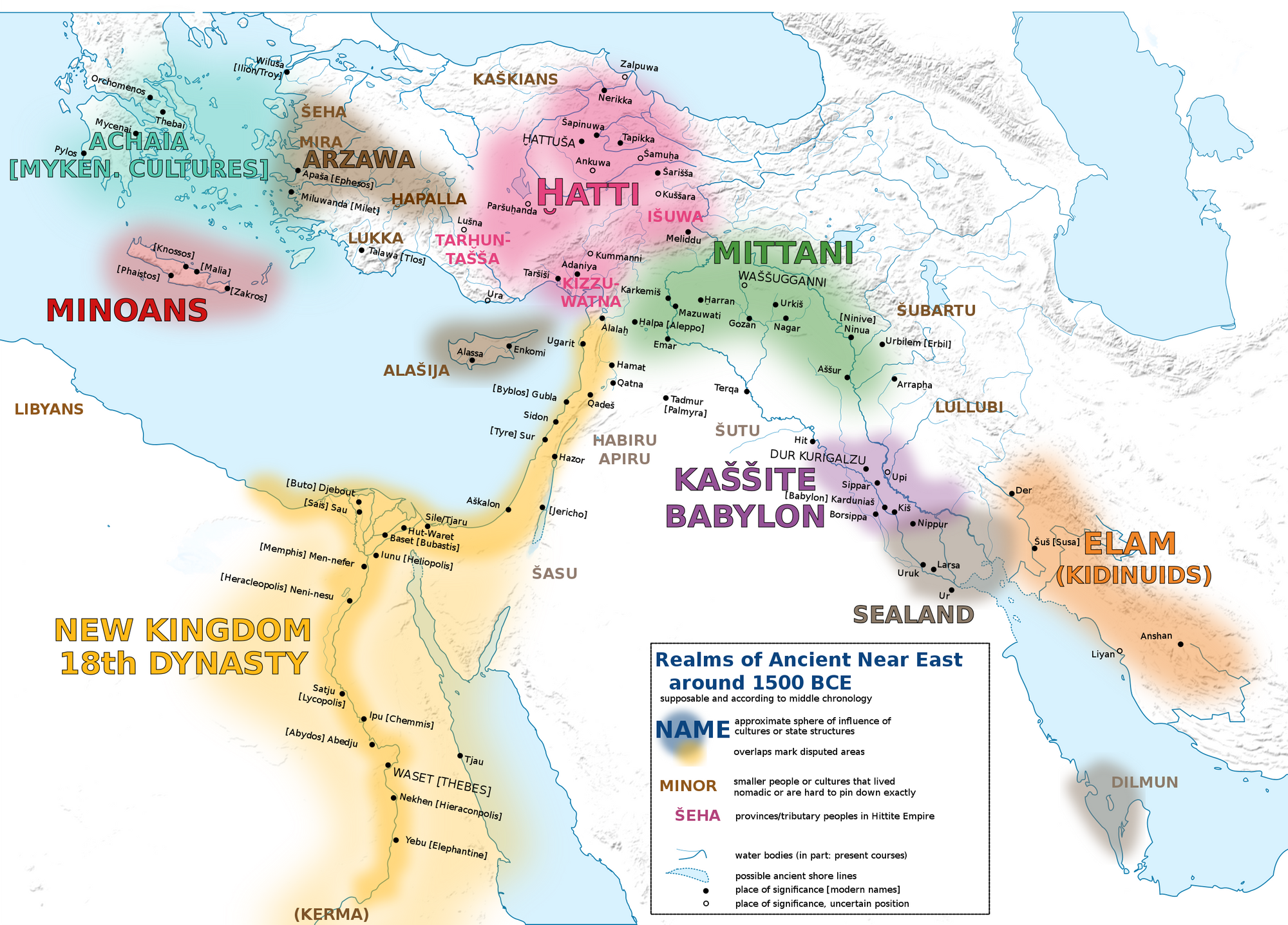

In Wilkinson’s estimation, several civilizations coexisted up until the 19th century, but today there’s a single, global civilization. This “Central Civilization” is a descendant of a civilization that emerged around 01500 BC when Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations collided and fused. Over the next 3,500 years, that civilization “then expanded over the entire planet and absorbed, on unequal terms, all other previously independent civilizations.”

Some civilizational mergers have involved groups seizing control over and incorporating other groups. But the linking of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations in the second millennium BC was an “atypical” and “egalitarian” coming together that, if Wilkinson has his history right, formed “a new joint network-entity” and differed from many future agglomerations involving annexation of one by civilization by another.

His somewhat idiosyncratic version of world-systems analysis and assessment of the longue durée frames the origins of what would much later become our globe-encircling “Central Civilization” as a fairly equitable encounter, on a certain level.

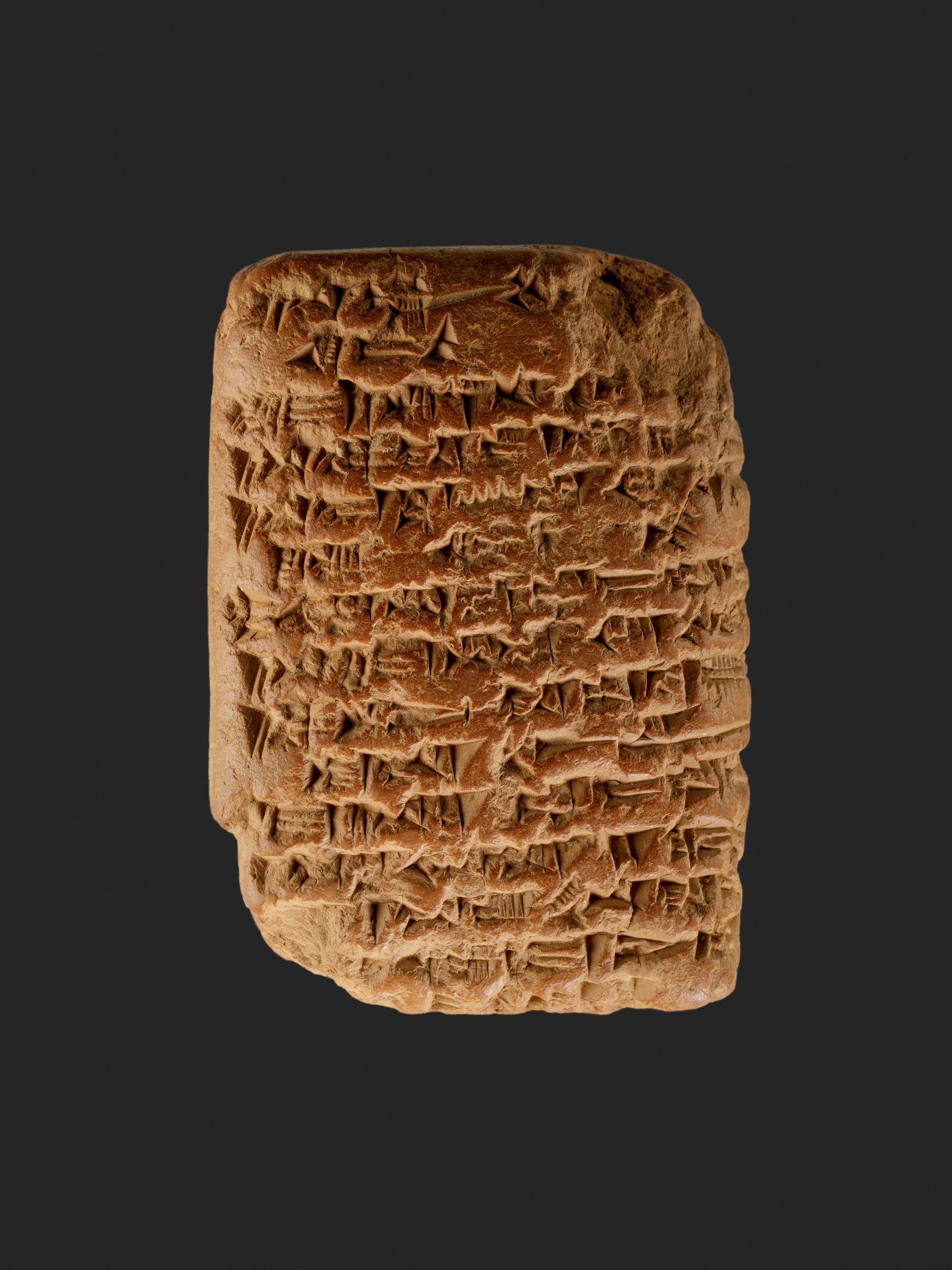

“The connection was made and maintained through mutually beneficial trade; politico-military independence and equality were preserved through the stalemating of imperialist war and the frustration of conquest,” Wilkinson explained. Records from Armana referring to gold from Egypt and royal daughters from states in Southwest Asia indicate they maintained exchange relations through a kind of luxury trade that nevertheless exacted a human toll.

The historical possibility of forging relations without domination can be seen as a source of hope — though these ancient civilizations came together via millennia-old realpolitik rather than humanitarian impulses.

As Wilkinson explained it, the merger of the two separate systems into one came as Egyptians aimed “to maintain multipolarity in southwest Asia,” and thus began treating the Mitanni kingdom in Mesopotamia not “as an external target for loot nor a potential subaltern to conquer, but as a useful check to balance the rising power of the Hittites, themselves far out of Egypt’s direct imperial reach.”

Over millennia, the network that formed at the intersection of Asia and Africa came to encompass networks to the west in Europe, the Americas, the western part of the African continent and in south and east Asia placing it, in certain respects, at the center of the world stage.

Five Centuries of European Domination

Christopher Chase-Dunn, sociologist and director of the Institute for Research on World-Systems at the University of California, Riverside, sees the existing system as more or less coeval with what’s considered the ascendance of the West. He follows the view of first-generation world-systems scholar Giovanni Arrighi, who claimed the modern capitalist world-system formed when Genoa and Portugal entered an alliance in the 15th century.

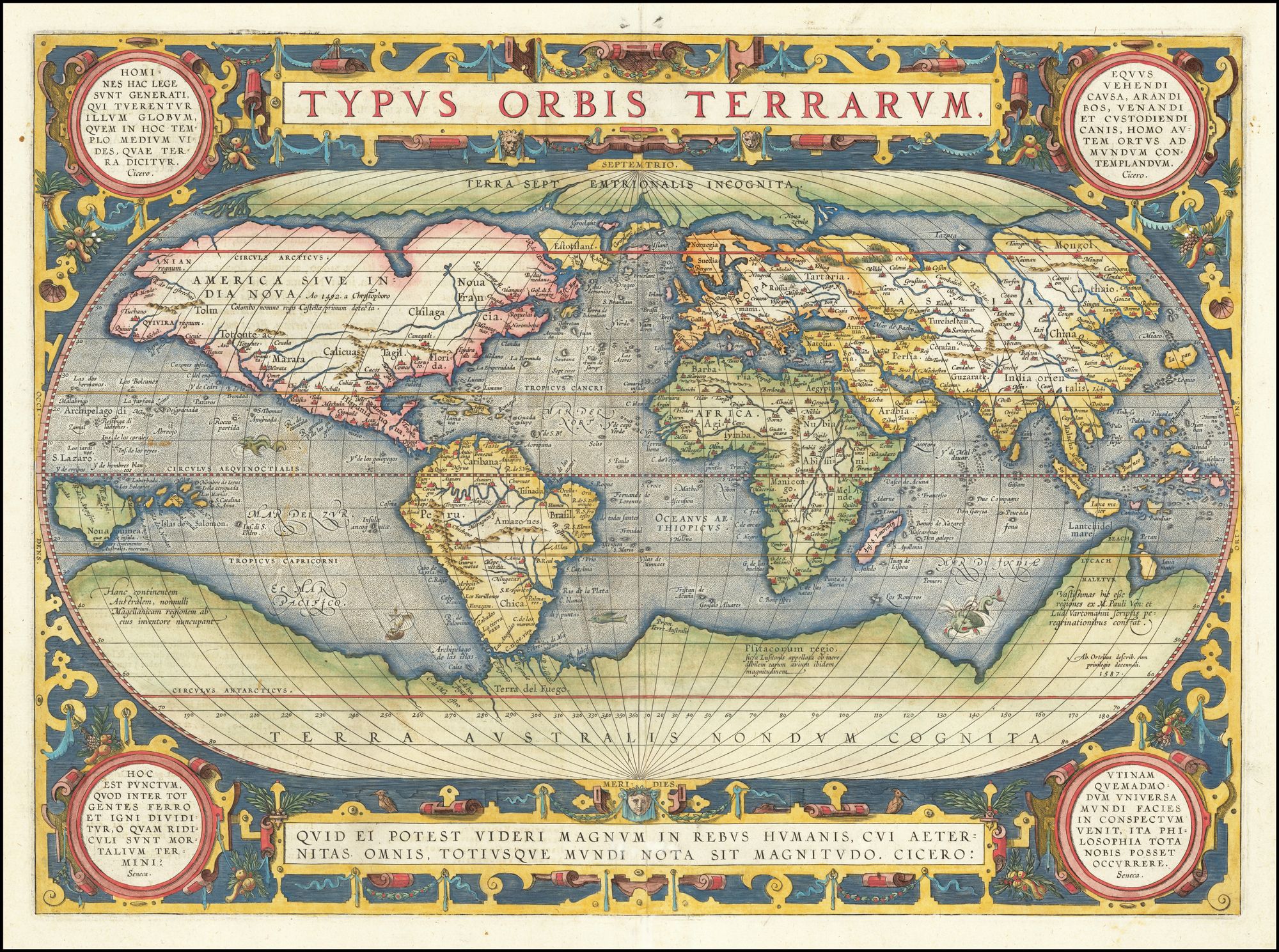

In a similar vein, Wallerstein argued in “The Modern World-System I,” that a “European world-economy” came into being in the late 15th and early 16th century. As a new “economic but not a political entity,” in his words, “unlike empires, city-states and nation-states,” within it, this social system was a “world” because it exceeded “juridically-defined political unit[s],” and a “world-economy” because economic relations formed the basis of connection that propelled its subsequent expansion across the globe.

Aviva Chomsky, a professor of history at Salem State University, explained how in a course she teaches at SSU, “Colonialism and the Making of the Modern World,” she draws on the late world-system scholar Janet Abu-Lughod’s “Before European Hegemony,” to explore the “Afro-Eurasian system of interlocking trade/communication spheres from East Asia to the Mediterranean/North Africa” that antedated 01492.

Similar to the Egypt-Mesopotamia partnering at the origin of the “Central Civilization,” in Wilkinson’s account, regions in that Afro-Eurasian system about 500 years ago participated, per Chomsky, with relative parity. But, she stresses, that didn’t equate to egalitarianism within them. To one degree or another, they were all “based on systems of forced/dispossessed labor, taxation,” which were, “extracted from the poor to serve the power, leisure, and consumption of elites.”

With the late-15th century rise of European hegemony — in other words, with the continent’s disproportionate influence and authority over other regions — there also arose “an Atlantic world system in which Europe, led by Spain and Portugal, conquers the Americas and develops the transatlantic slave trade, with devastating consequences for the peoples of Africa and the Americas,” Chomsky said.

World-systems scholars use language of “core” and “periphery” zones and processes, referring to the relations of operation, leverage, and control that benefit some nation-states at the expense of others. Certain nation-states or similar entities can at times obtain control over the system at large, and they call this dominance hegemony. Its full realization is considered relatively rare. Wallerstein, Chase-Dunn and others believe the United Provinces of the Netherlands became a hegemonic core power circa the 17th century, as they achieved overwhelming trading power in the fledgling market economy.

Two other powers are thought to have achieved serious hegemonic status over the longue durée of our current, now crisis-riddled system. Their hegemony and hegemonic declines coincided with significant changes in the workings of the world.

A New System Of Exploitation

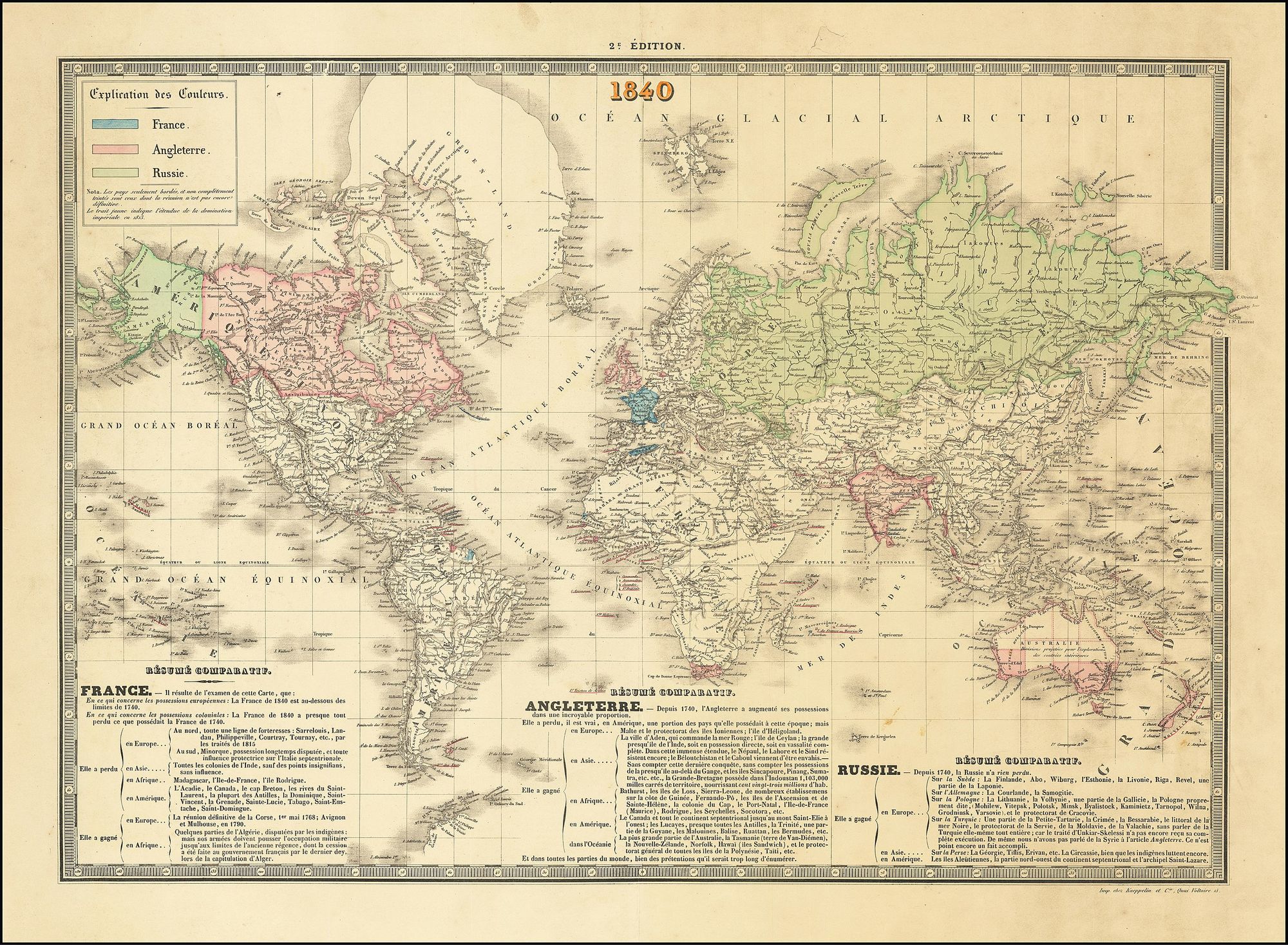

As northern European nations started to take over the slave trade and extend colonization “into the peripheries of Asia,” the Spanish and Portuguese empires declined, according to Chomsky’s reading. Then, “the shift accelerates in the [01800s] as a new ‘world system’ emerges,” the newly “independent United States joins with (primarily) Britain, France, [and] the Netherlands to establish colonial hegemony in the Americas, Africa, and much of Asia.”

Awass said in a late December 02022 interview that core regions intervened in the periphery in a direct way during the colonial period. “In a sense, they intervene[d] directly by taking over many countries or getting capitulations from countries that [they] could not take over directly, like the Ottoman Empire, or the Chinese Empire, Japan and Thailand, for example,” he said.

A key factor in this system was the exploitation of the natural resources of the periphery by the core. During this period, non-European industrial production suffered, Chomsky explained, as the other regions succumbed to pressures to export raw materials like cotton, copper, coal, tin, petroleum, and palm oil to Europe, as well as to the United States.

As it assumed a hegemonic position within the world-system in the 19th century, Britain became home to the expansive factory labor, employment, and production that horrified and fascinated thinkers like Marx, who wrote extensively about British manufacturing as he tried to understand and explain the engine of the system.

Britain’s dominance waned by the 20th century when a new world power attained what Wallerstein considered the most “extensive and total” exercise of hegemony and established conditions for what “promises to be the swiftest and most total” decline.

The U.S., Alone

Most anyone who uses world-systems theory, and many who don’t, agree that after World War II, the United States emerged as a hegemonic power.

In this era, as Chomsky framed it, decolonized people achieved “nominal political independence” but faced overwhelming resistance in a struggle for an alternative economic order. The Cold War helped justify the United States in crushing attempts to redress the system and ex-colonial powers maintained “unequal exchange” and retained control of trade and financial institutions at the international level.

Awass has tried to model the world-system as a “Global Power-Field,” or GPF, drawing attention to important forces that covertly perpetuate and reshape global relations of control and subordination. His concept of “nonlocality” highlights how after decolonization the reshaping of the field made it so core powers no longer needed to remain present in peripheral regions to control or exploit them.

“It was these institutions and the rules of this new global field that everybody now had to play by because they joined the international nation-state system and all of the different global bodies, like the United Nations, which was an acknowledgment of this international nation-state system, and they set up the rules of the game, and just let the rules operate to their favor,” he said.

Revolution, Reaction, and Reorganization

The supreme hegemony the United States exercised did not last long. Wallerstein held that as the most expansive phase in a cycle of the capitalist world-economy gave way to a downturn, it coincided with the commencement of American hegemonic decline. It was no accident, in his view, that social movements and popular revolts reflected and expressed world-historical changes around that time.

“He was at Columbia University when the student movement in 01968 erupted,” notes David Martinez, a documentarian at work on a project about Wallerstein’s ideas, later adding: “He was a young professor at Columbia, and he was actually on the committee of teachers to work with the students. That's when he saw that the movements of 01968 were of world historical importance.”

Various uprisings converged in what world-system theorists, following Wallerstein, call the 01968 “world revolution,” which Wallerstein thought foregrounded new developments in the analysis and orientation of anti-systemic movements.

Striking workers and students in Paris almost ushered in another French revolution that year in May. Come August, Soviet-directed forces invaded Czechoslovakia to crush the “Prague Spring” movement that tried to create “socialism with a human face.” In the United States, organizations like Students for a Democratic Society and the Black Panther Party influenced communities as well as popular culture, and the demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago put police violence on full display following a solid year of protests and riots that engulfed cities throughout the country. Authorities also shot into a crowd of thousands of student activists in the streets of Mexico City that October just before the start of the Olympics.

Intensified resistance to US aggression in Vietnam, punctuated by the Tet Offensive that kicked off the year of “world revolution,” revealed new limits on the reigning superpower’s military might, portending a waning of hegemony. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union faced scrutiny for colluding with the United States in Cold War maintenance of geopolitical power. Organizers called into question the strategy of seizing state power as the necessary initial step in trying to improve conditions and world relations, and they emphasized the oft-ignored aims and concerns of people marginalized because of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality.

Liberalism entailed an assumption about the possibilities for continued human progress and uplift within the established hegemonic order, but the revolutionary upheaval of 01968 ended the tenuous triumph of the “centrist liberalism” that had dominated, Wallerstein thought, “for a good hundred-odd years.”

The displacement of that previously dominant ideology epitomized and propelled what Wallerstein conceived of as the system’s ongoing phase of structural crisis. Yet these last few decades of crises might also foretell new possibilities for the next turn of the world-system.

Andre Gunder Frank understood the coming crisis as denoting both “danger and opportunity.” In his 01998 book, “ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age,” he forecast a coming period wherein East Asia would regain its preeminent world-economic position, and he claimed that “a time of crisis, especially for the previously best-placed part of the world economy/system, also opens a window of opportunity for some — not all! — more peripherally or marginally placed ones to improve their own position within the system as a whole.”

Indeed, the impetus and reverberations of the “world revolution” in 01968 foregrounded the concerns of the previously peripheral and marginal, at least at the cultural or ideological level, in Wallerstein’s reading. Those movements intimated another possible world(-system) with different popular values. They prefigured future and indeed current social movements, but they also elicited an enduring reactionary response.

When social upheavals ensued and crises emerged around 01970, major players in the global system made moves to retain their dominance that arguably initiated or accelerated all those previously mentioned trends.

Awass has written about the role of U.S. “dollar hegemony” post-WWII. The United States’ formal replacement of the gold standard with the dollar standard in early 01970s could have brought about a decisive end to American hegemony, as states outside of the Western core began to grumble about the dollar’s place as a fiat currency. In Awass’ analysis, the United States’ maintenance of hegemony was achieved by striking a deal in 01974 with Saudi Arabia, offering the regime protection. In exchange, the kingdom used its standing as the quasi-official leader of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, pressuring them to accept only the dollar in exchange for oil, which allowed the United States to continue to leverage power through the monetary system.

In his article, Awass pointed to US.-imposed sanctions on Iran as further evidence of a core power trying to maintain control with little regard for human consequences, though his piece focused on macro-modeling.

“I didn't highlight those dimensions of how it worked at the micro level of Iran, for example, on the second levels of the sort of sanctions that were taking place there, but for God's [sake], I mean, people can't even afford medicine,” he said.

The collapse of the Soviet Union near the close of the 20th century didn’t exactly spell “The End of History,” but it did temporarily reinforce the power of a descending hegemon in a volatile world order.

“After 01989 there is really no check at all left on US hegemony,” Chomsky added, “and the neoliberal order is imposed full-scale, with the Third World subject to structural adjustment, the dismantling of the social welfare state at home and abroad, deindustrialization of the core and maquiladorization, extractivism, tourism, and call centers as the new development strategies for the periphery. Meanwhile the impact of the industrial project comes home to roost with climate chaos, mass migration, [xenophobia] and hardened borders.”

What Comes Next?

Following Wallerstein’s analysis, the cost of the waste associated with economic production can no longer be so easily externalized by the businesses and industries producing it, given greater popular pressure to challenge pressing ecological injustices and curb the climate disruption driven by those externalities of capitalist production. That pressure further raises the cost of doing business within the existing system, which in turn contributes to the chaotic downturn and fluctuations characteristic of structural crisis.

For Chase-Dunn, the ongoing “contradictions of capitalism and decline of US hegemony” could contribute to “further renewal of inter-state warfare,” climate crises, and possible “deglobalization” of the global economy – possibly leading to collapse of the financial system in the next few decades.

To pursue a facet of Wallerstein’s work that seems especially urgent now, Chase-Dunn, along with Rebecca Alvarez, put together a proposal for a political vehicle that could combine the participatory elements of horizontal organization, free from top-down authority, together with a transnational steering structure. Via “The Vessel,” affinity groups and local communities could share the results of their work, facilitate collaboration, formulate visions for social change, determine preferable strategies as well as tactics, and coordinate global collective action, campaigns, and mobilizations through a delegated council. Perhaps this organizational ark or ship is capable of navigating through the proverbial flood ready to wash out a perturbed world-system during whatever kind of transitional period we’re in at present, provides one possible antidote to the preponderance of influence exercised among small slivers of the population within the confines of the interstate nexus and capitalist world-economy.

People could also carve out and coordinate a network of physical and digital spaces where care and cooperative decision-making gives everyone the ability to influence institutions, policies, relations and actions that affect them. Those spaces might embody and popularize values that could prevail over the outmoded ones embedded in the capitalist world-economy.

Similarly, Awass mentioned “courage,” “gumption” and “moral cultivation” as likely prerequisites for effective political action going forward. He acknowledged setbacks in struggle, like the crushing of the Arab Spring movement and the overturning of many of its achievements. “I think there perhaps are some positive signs of increasing global solidarity,” he qualified, referencing international climate justice activism while also lamenting forces that tend to circumvent such efforts.

Aviva Chomsky in turn recommended a piece by Jason Hickel on de-growth and anti-colonial politics as a source of ideas for action.

“In terms of what we can [or should] do now, I think that understanding the relationship between racism, colonialism, and climate chaos leads us to remaking the global industrial order with [degrowth] in the global north as a component of reparations for the ongoing damages,” she shared.

Until his death, Wallerstein argued the system had entered a structural crisis. Given our pivotal juncture, what every person “does at each moment about each immediate issue matters,” as he wrote in a 02013 commentary, again invoking the “butterfly effect” while likening all of us to “little butterflies today.” The end of the capitalist world-economy, he insisted, is coming; it’s just a matter of how and when.

“What it turns into could be something with basically all the worst features with none of the good features, or the opposite, the good features with none of the bad features,” Martinez said, conjuring the spirit of Wallerstein’s critical optimism. “Our job is to make sure that it's the latter that happens, that it turns into something better.”